| Original research | Peer reviewed |

Cite as: Canning P, Costello N, Mahan-Riggs E, et al. Retrospective study of lameness cases in growing pigs associated with joint and leg submissions to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory. J Swine Health Prod. 2019;27(3):118-124.

Also available as a PDF.

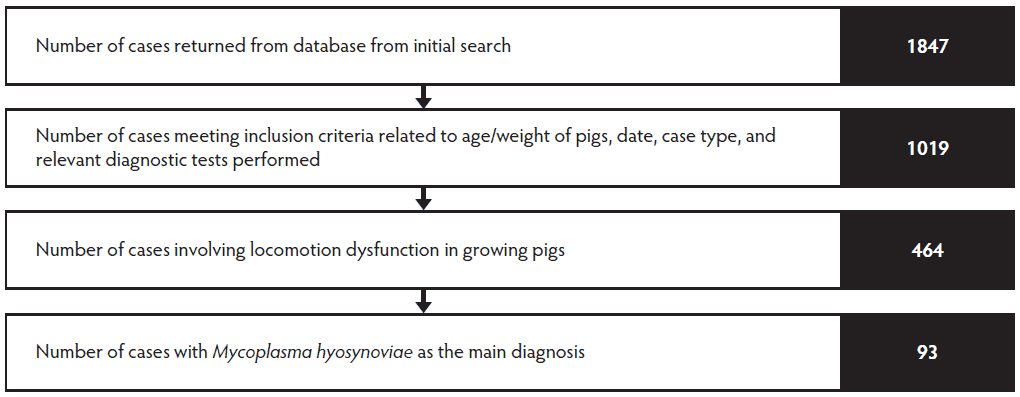

SummaryObjective: The objective of this study was to categorize and quantify the most common causes of joint- or leg-associated lameness by summarizing available information from cases presented to the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISU VDL) between 2010 and 2015. Materials and methods: All cases of lameness or locomotor dysfunction in 7- to 40-week-old pigs submitted to the ISU VDL between May 1, 2010 and April 30, 2015 were retrieved. After removing cases that did not meet the inclusion criteria, the remaining cases were individually reviewed and assigned a primary and secondary diagnosis. Results: Of the 1847 cases retrieved, 464 met the inclusion criteria. The 4 most common primary diagnosis categories were Mycoplasma hyosynoviae (93 cases; 20%), metabolic bone disease (86 cases; 18.5%), infectious arthritis due to non-Mycoplasma bacterial infection (81 cases; 17.5%), and lameness with inconclusive findings (101 cases; 21.8%). There were 23.3% of the cases (108 of 464 cases) that had a secondary diagnosis with metabolic bone disease (28.7%; 31 of 108 cases) identified as the most common secondary diagnosis. Implications: This study reinforces the importance of careful clinical examination, proper sampling, and confirming causes with appropriate diagnostic testing for accurate diagnosis of lameness. | ResumenObjetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue categorizar y cuantificar las causas más comunes de cojera asociada con la articulación o la pierna resumiendo la información disponible de los casos enviados al Laboratorio de Diagnóstico Veterinario de la Universidad del Estado de Iowa (ISU VDL por sus siglas en inglés) entre 2010 y 2015. Materiales y métodos: Se recuperaron todos los casos de cojera o disfunción locomotora en cerdos de 7 a 40 semanas de edad enviados al ISU VDL entre el 1 de mayo de 2010 y el 30 de abril de 2015. Después de eliminar los casos que no cumplían con los criterios de inclusión, los casos restantes se revisaron individualmente y se les asignó un diagnóstico primario y uno secundario. Resultados: De los 1847 casos recuperados, 464 cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión. Las 4 categorías de diagnóstico primario más comunes fueron Mycoplasma hyosynoviae (93 casos; 20%), enfermedad ósea metabólica (86 casos; 18.5%), artritis infecciosa debida a infección bacteriana no relacionada con Mycoplasma (81 casos; 17.5%) y cojera sin hallazgos concluyentes (101 casos; 21.8%). Un 23.3% de casos (108 de 464 casos) tuvieron un diagnóstico secundario relacionado con enfermedad metabólica ósea (28.7%; 31 de 108 casos), identificado como el diagnóstico secundario más frecuente. Implicaciones: Este estudio refuerza la importancia de un examen clínico cuidadoso, un muestreo adecuado y la confirmación de las causas con pruebas de diagnóstico apropiadas para un diagnóstico preciso de la cojera. | ResuméObjectif: L’objectif de la présente étude était de catégoriser et quantifier les causes les plus fréquentes de boiteries associées aux articulations ou aux pattes en résumant les informations disponibles des cas présentés au Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISU VDL) entre 2010 et 2015. Matériels et méthodes: Tous les cas de boiterie ou de dysfonction locomotrice chez les porcs âgés de 7 à 40 semaines soumis au ISU VDL entre le 1er mai 2010 et le 30 avril 2015 furent récupérés. Après avoir retiré les cas qui ne rencontraient pas les critères d’inclusion, les cas restants furent individuellement revus et on leur assigna un diagnostic primaire et secondaire. Résultats: Des 1847 cas récupérés, 464 rencontraient les critères d’inclusion. Les quatre catégories de diagnostic primaire les plus fréquentes étaient Mycoplasma hyosynoviae (93 cas; 20%); maladie osseuse métabolique (86 cas; 18.5%); arthrite infectieuse bactérienne due à une infection autre qu’à Mycoplasma (81 cas; 17.5%), et boiterie avec trouvailles non-concluantes (101 cas; 21.8%). Il y avait 23.3% des cas (108 des 464 cas) qui avaient un diagnostic secondaire, et une maladie osseuse métabolique (28.7%, 31 des 108 cas) a été identifiée comme le diagnostic secondaire le plus fréquent. Implications: Cette étude montre l’importance d’un examen clinique minutieux, d’un échantillonnage adéquat, et de confirmer les causes avec un diagnostic approprié afin d’obtenir un diagnostic précis lors de boiterie.

|

Keywords: swine, Mycoplasma hyosynoviae, lameness, arthritis, case series

Search the AASV web site

for pages with similar keywords.

Received: August 3, 2017

Accepted: November 6, 2018

Joint- and leg-associated lameness in growing pigs is a common diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for swine veterinarians. A diagnostic investigation usually starts when the caretaker identifies lameness in a group of pigs and notifies a veterinarian. The veterinarian will perform an assessment, which may involve submission of samples to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory (VDL). In recent years, there has been a great interest in Mycoplasma hyosynoviae (MHS), which is considered one of the major primary causes of joint-associated arthritis, but the organism may only be present transiently within the joint making diagnosis challenging.1 Inconclusive diagnostic testing increases uncertainty of diagnosis and decreases confidence in specific recommendations for therapy. Sample submissions that do not generate actionable information or support a specific etiology for the lameness are reported by practitioners, but the frequency of these cases from VDL submission databases has not been quantified and reported in the peer-reviewed literature.

Increasing regulation and oversight of antimicrobial use in swine reinforces the value of an accurate diagnosis to support treatment decisions and prudent antimicrobial use. While diagnostic laboratory data is not equivalent to field prevalence, it is helpful for swine practitioners to be aware of the spectrum and relative frequency of lameness causes as reported by a Midwestern VDL. Insight into capabilities and expectations of laboratory testing can assist veterinarians in proper sampling, test selection, interpretation of results, and provide insights into the relative importance of specific lameness etiologies for future research priorities. Specifically, insights from a study of submission trends and diagnostic approaches for cases of acute MHS synovitis may inform improvements in sampling and testing for this common etiology of growing pig lameness. Beyond general recommendations in swine texts, there is limited published information on submission practices for joint-associated lameness cases.2

The primary objective of this study was to categorize and quantify the most common causes of joint- or leg-associated lameness by summarizing available information from cases presented to the Iowa State University (ISU) VDL between 2010 and 2015. The second objective of this study was to summarize submission trends and features of those cases with an MHS diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Laboratory diagnostic submissions from the ISU VDL were used for this study, so no Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval was needed. All cases of lameness or locomotor dysfunction submitted to the ISU VDL between May 1, 2010 and April 30, 2015 were retrieved for review using the ISU VDL laboratory information management system (LIMS). Each individual laboratory accession was considered a single case irrespective of number of samples submitted. Inclusion criteria were selected with the aid of VDL diagnosticians and information technology specialists. All cases were individually reviewed to ensure each met the inclusion criteria: species (porcine), age or weight (7-40 weeks or >16 kg), case type (field case), histopathology performed, and at least one diagnostic code assigned by a diagnostic pathologist. The 23 diagnostic codes and diagnostic assays that were used to search the LIMS for lameness cases are presented in Table 1. If the age or weight was not present in the data output from LIMS, the case remained in the database and the original submission sheet was reviewed for any information that referenced age or weight. If no age or weight data was included on the submission sheet, the case was removed. Cases must have included joint tissue for histology to be included in this study. Cases involving serum, oral fluids, or swabs only were excluded.

Table 1: Swine diagnostic codes and diagnostic assays used as inclusion criteria for cases of lameness or locomotor dysfunction submitted to the ISU VDL

| Diagnostic codes | Joint arthritis, idiopathic |

|---|---|

| Joint arthritis, Actinobacillus suis | |

| Joint arthritis, Truperella pyogenes | |

| Joint arthropathy | |

| Joint arthritis, bacterial, miscellaneous | |

| Joint arthritis, Escherichia coli | |

| Joint arthritis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | |

| Joint arthritis, Haemophilus parasuis | |

| Joint arthritis, Mycoplasma species | |

| Joint arthritis, Mycoplasma hyorhinis | |

| Joint arthritis, Mycoplasma hyosynoviae | |

| Joint arthritis, non-suppurative | |

| Joint osteochondrosis | |

| Joint arthritis, Staphylococcus species | |

| Joint arthritis, Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Joint arthritis, Streptococcus species | |

| Joint arthritis, Streptococcus suis | |

| Joint arthritis, suppurative | |

| Calcium deficiency | |

| Vitamin D deficiency | |

| All bone osteopathies | |

| Septic Mycoplasma hyorhinis | |

| No diagnosis | |

| Diagnostic tests/assays | PCR-Mycoplasma hyosynoviae Mycoplasma culture |

For each qualifying accession, the submission form and laboratory report were reviewed and relevant information extracted into a spreadsheet. Information extracted from the LIMS included accession number, submission date, pig age, diagnostic code, diagnostician, histopathology observations, and all tests performed with results. The clinic and bill party information were used to remove those cases that were not diagnostic investigations of field cases, such as research and teaching accounts. Client name, submitting veterinarian, and premises identification were not extracted from the database to maintain confidentiality and anonymity.

To confirm that all qualifying cases did involve lameness and locomotion dysfunction, additional information from the submission sheet and final report was entered into the spreadsheet manually. The history, submission notes, and the final diagnosis and comments from the diagnostician on the final report were entered and evaluated. Specifically, the case had to include terms involving lameness or locomotion in the history and the completed diagnostic testing had to be relevant to locomotion dysfunction, lameness, or joint disease. For example, a case may have Mycoplasma hyorhinis (MHR) septicemia as a diagnostic code, but if the history did not report any information related to lameness and legs or joints were not submitted with the case, then the case was excluded.

Assigning primary and secondary diagnosis

After confirming that all cases remaining in the database involved locomotion dysfunction and met the inclusion criteria, the cases were individually reviewed and assigned a primary diagnosis and, when diagnostic criteria for more than one category was present, a secondary diagnosis. Specific criteria were created for each diagnosis and applied uniformly to the cases (Table 2). Unless designated as “if available” in Table 2, all criteria listed for a given category must have been satisfied for the diagnosis to be assigned to a case. Criteria for each diagnosis were determined by peer-reviewed literature and consultation with an ISU VDL diagnostician. Primary diagnosis refers to the findings in the case that are understood, to the best of the assessor’s knowledge, to be the main or most acute cause of the lameness. Secondary or “other” diagnosis refers to a diagnostic category that was relevant to the case but was not the main or most acute cause of lameness. This determination was made from comments in the final report by the diagnostician, severity and prevalence of the abnormalities, and understanding of the pathophysiology of the given diagnostic category in question. Primary and secondary diagnostic categories were assigned to the entire submission, not each individual pig within a case.

Table 2: Diagnostic criteria for each diagnostic category applied to cases associated with joint or leg lameness

| Diagnostic category | Criteria for diagnostic category inclusion |

|---|---|

| Lameness with inconclusive findings (abnormal diagnostic testing results with inconclusive findings) | Lameness reported by practitioner or diagnostician Histology of joint revealed mild non-specific changes to the synovial tissue Additional testing not performed, or results of additional testing were inconclusive or not significant Description of inconclusive or nonspecific joint changes included in final report by pathologist [if available*] |

| MHS | Specimens submitted from animals with clinical lameness, joint swelling, or both At least one positive MHS PCR result on joint fluid or joint tissue Histology lesions consistent with MHS as per diagnostician comments in histology report or published histology findings associated with experimental and field MHS cases1,3,4 |

| Metabolic bone disease | Abnormal results on any calcium, phosphorus, bone histopathology, vitamin D assay, or bone ash/density tests. Not all assays listed had to be performed to be included in the metabolic bone disease category Diagnostician comments that abnormality is contributing to locomotion issues |

| Infectious arthritis (bacterial, non-Mycoplasma species) | Histology on synovium indicative of infectious (non-Mycoplasma) process Significant findings on culture† Gross description of fluid indicative of infection, ie, purulent, serosanguinous [if available*] Positive PCR results on molecular testing for Erysipelothrix species or Haemophilus parasuis from joint specimens [if available*] |

| Lameness: no abnormal findings | Lameness reported by practitioner or diagnostician Culture with no significant findings† MHS PCR negative Histology of joint revealed no changes to synovial tissue |

| Osteochondrosis | Gross or histologically observed cartilage defects in articular cartilage |

| MHR | MHR PCR positive or MHR culture positive on joint fluid or joint tissue Histological changes to the synovium consistent with MHR Systemic gross and histological lesions from other tissues submitted indicative of systemic MHR cases [if available*] Serosanguinous synovial fluid or fibrin in synovial fluid [if available*] |

| Trauma | Fractures unrelated to abnormal bone histology indicative of metabolic bone disease OR Bursitis related to physical contact with slats, as associated in diagnostician comments |

| Osteomyelitis | Bacterial infection of the bone as per gross or histological assessment of the bone Significant findings on culture [if available*] |

* Indicates that for some cases, this information or specimen may not be available or that relevant tests for this diagnostic category may not have been performed.

† Significant findings refer to growth of a bacterial species associated with arthritis as per the bacteriologist or published literature.

MHS = Mycoplasma hyosynoviae; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; MHR = Mycoplasma hyorhinis.

Description of submission characteristics for Mycoplasma hyosynoviae cases

Cases that were assigned MHS as the primary diagnosis were then further reviewed to summarize case attributes related to submission habits. Specifically, the following data were collected and summarized: submission year, inclusion of a history on submission sheet (yes or no), inclusion of differential diagnosis in history (yes or no), number of differential diagnoses included in history, type and number of specimens submitted, number of MHS polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays performed per case, number of animals from which the submitted specimens were procured, number of diagnostic tests requested, types of diagnostic tests requested, results from non-MHS related tests performed, and secondary diagnosis.

Results

Primary and secondary diagnosis for all lameness cases

The results of each step of the case database creation process are presented in Figure 1. The primary and secondary diagnosis associated with each of the 464 lameness cases is summarized in Table 3. The four most common primary diagnoses were almost equally represented: MHS (93 cases; 20%), metabolic bone disease (86 cases; 18.5%), infectious arthritis due to non-Mycoplasma bacterial infection (81 cases; 17.5%), and lameness with inconclusive findings (101 cases; 21.8%). Of the 23.3% of cases that had a secondary diagnosis (108 of 464 cases), metabolic bone disease was identified as the most common (28.7%; 31 of 108 cases).

Figure 1: Summary of case selection process from a retrospective survey of lameness cases from the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory between May 2010 and April 2015

Table 3: Primary and secondary diagnoses for 464 lameness cases in growing pigs from a retrospective case survey at the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory between May 2010 and April 2015

| Diagnosis | Primary diagnosis | Secondary diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, No. | Cases, % | Cases, No. | Cases, % | |

| Lameness with inconclusive findings | 101 | 21.8 | 27 | 25.0 |

| Mycoplasma hyosynoviae | 93 | 20.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Metabolic bone disease | 86 | 18.5 | 31 | 28.7 |

| Infectious (bacterial) | 81 | 17.5 | 18 | 16.7 |

| Lameness: no abnormal findings | 43 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Osteochondrosis | 29 | 6.3 | 18 | 16.7 |

| Mycoplasma hyorhinis | 19 | 4.1 | 4 | 3.7 |

| Trauma | 10 | 2.1 | 8 | 7.4 |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Total | 464 | 100 | 108 | 100 |

Summary of submission characteristics for Mycoplasma hyosynoviae cases

The number of MHS diagnosed cases per full calendar year ranged from 7 cases in 2011 to 34 cases in 2013. A review of case characteristics revealed that the mean age of pigs diagnosed with MHS was 18.3 weeks (range, 10-32 weeks). A mean of 2.4 MHS PCR assays were conducted per MHS case (range, 1-26 assays). The cycle threshold values for MHS PCR ranged from 20.3 to > 44. Cycle threshold values > 44 were considered negative for MHS at the ISU VDL. For cases requesting 3 or more MHS PCR tests (n = 29), the mean percentage of MHS-positive PCRs was 54.7%.

Seventy-one percent (66 of 93) of cases listed differential diagnoses with their submission form and of these, 80.3% (53 of 66 cases) listed multiple possible differential diagnoses. Nine cases (9.7%) listed MHS as the sole differential. Of the 53 cases that listed more than one differential, the most common differentials were MHS (71.7%; 38 cases), MHR (41.5%; 22 cases), Haemophilus parasuis (41.5%; 22 cases), Streptococcus suis (39.6%; 21 cases), and Erysipelothrix species (35.8%; 19 cases). Metabolic bone disease, osteochondrosis (OCD), and trauma were listed 19 (35.8%) times cumulatively.

The majority (68.8%; 64 of 93) of submitting veterinarians selected diagnostic testing to be at the discretion of the VDL diagnostician, while 15.1% (14 of 93 veterinarians) left the test selection portion of the diagnostic form completely blank. Another 16.1% (15 of 93) of submitting veterinarians selected at least four unique diagnostic tests for their case.

Sample types submitted included 43% (40 of 93) of cases with at least one whole leg, 26.9% (25 of 93) with at least one whole pig, and 24.7% (23 of 93) with at least one joint swab or fluid. The mean number of legs submitted per case was 3.7 legs (range, 1-14 legs). Ninety percent (36 of 40) of cases were submitted with at least 2 legs and 45% (18 of 40) of cases were submitted with 3 to 8 legs. The mean number of whole pigs submitted per case was 4.4 whole pigs (range, 1-25 pigs). Thirty-six percent (9 of 25) of cases were submitted with 2 whole pigs, 28% (7 of 25 cases) were submitted with 3 to 5 pigs, and 28% (7 of 25 cases) were submitted with 6 or more pigs. Considering all sample types, submissions contained samples from a mean of 2.9 animals (range, 1-25 animals).

Of the 93 cases where MHS was the primary diagnosis, 30 (32.3%) cases had multiple diagnoses, with OCD (26.7%; 8 of 30 cases) and non-Mycoplasma bacterial infection (26.7%; 8 of 30 cases) being the most common secondary diagnosis.

The most commonly requested test for pathogens other than Mycoplasma species was aerobic culture and the mean number of cultures per case was 2.4 (range, 1-37 cultures), of which 77.7% (171 of 220 total cultures) returned no significant growth. This does not include Erysipelothrix specific cultures. Erysipelas was commonly listed as a differential (35.8%; 19 of 53 cases) but none of the cases listed skin lesions as part of the history or gross lesion findings. Almost half (45 cases) of the 93 MHS cases had at least one Erysipelothrix culture or PCR performed, with a mean of 2.5 Erysipelothrix assays per case. Of these 45 cases, however, only 1 (2.2%) returned a positive result.

Discussion

This study summarizes the most frequently observed lameness diagnostic categories for case submissions involving joints and legs at the ISU VDL between 2010 and 2015. A similar study reported the frequency of diagnosis of arthritis, specifically MHS and MHR cases, between 2003 and 2010 at the ISU VDL.5 There were 431 clinical cases with infectious arthritis during that time period and MHS represented 17% of the arthritis cases.5 There were more MHR cases identified in that study than reported here, but that study included pigs < 7 weeks of age. Findings from the current study are also consistent with another summary of arthritis cases from 2003 to 2014 at the ISU VDL.6 This study found that 25% of the cases were idiopathic, 20% were MHS, 24% bacterial and 12% were MHR based on the diagnostic code alone.6 These results reinforce that many diagnostic investigations do not reveal a clear etiology of the lameness as a consequence of diagnostic testing alone.

Although these two studies are similar in topic to the current study, there are key distinctions between these papers and this retrospective review.5,6 For example, one study was a diagnostic note on cases between 2003 and 2010 and focused on recommendations for diagnosing Mycoplasma-associated arthritis.5 Since that time frame there has been development of additional PCR tests for Mycoplasma species associated with arthritis available at ISU VDL and lameness in growing pigs, particularly MHS, has become an emerging issue within the swine industry. Thus, an updated retrospective review is warranted. Another publication on lameness submissions to ISU VDL reflected a more current timeframe but is a conference proceeding and not available publicly.6 Both of these articles do not provide information about how the relevant diagnostic lab data was procured from the lab information management system, include information about inclusion/exclusion criteria, or require histology as part of the case. These comparable studies provide pilot information about the number of lameness cases and the types of primary diagnosis found but do not apply a systematic diagnostic criterion consistently across cases. This study focused on cases for which sufficient testing (histology, for example) was performed to diagnose MHS and then described characteristics of that subset of submissions.

Studies aiming to summarize lameness etiologies have been performed in the context of field cases. One Danish study looked at the microbiological causes of lameness in pigs at slaughter in Denmark. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae and MHS each comprised about 10% of the cases, while 70% of joints were sterile. Gross changes to the joints were observed with E rhusiopathiae and MHS associated arthritis but gross pathological changes in the sterile joints were non-specific.7 In another Danish slaughter pig study, MHS was isolated from 60% of the pigs with arthritis in three of the five herds. Claw lesions (22%) and severe OCD (10%) made up the second and third most common diagnosis across all herds.8

This study supports that MHS is an important contributor to arthritis, but there are several other important known and unknown etiologies associated with lameness.9 In this study, four diagnostic categories (lameness with inconclusive findings, MHS, metabolic bone disease, and non-Mycoplasma bacterial infection) accounted for 77.8% of the cases and 23.3% of these cases had at least one other lameness-associated abnormality. This reinforces that lameness is often multifactorial, and that many swine lameness pathological processes may be cumulative contributing to the difficulty in assigning a single etiology causation. Additionally, the high rate of lameness with inconclusive findings and non-infectious lameness cases should prompt practitioners to perform complete diagnostic investigations before implementing expensive interventions or antibiotic treatment in the field. Generally, most of the culture results indicated no significant growth. It can be challenging to interpret the diagnostic significance of this finding because a negative culture result could occur under several circumstances. For example, use of non-Mycoplasma specific culture media, the timing of when the bacteriological sample was collected with respect to the stage of disease in the animal, improper handling of bacteriological samples during transport, or that bacterial arthritis was not a contributor to the disease state of the joint would be potential explanations. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the cause of the negative cultures could not be identified and further analyzed. However, the diagnostic criteria used in this study support that histology is a key tool to provide context to culture and PCR findings.

Lameness with inconclusive findings was the most commonly assigned (21.8% of cases) diagnostic category for this study. It is possible that submitter bias through inappropriate animal selection, sample selection, sample handling, or test selection could artificially increase this number. For example, in cases where practitioners submitted one intact joint, it could be possible that with additional specimens, the case could have received a diagnosis.

Conclusions obtained by retrospective description of data from a VDL should be approached carefully. The data utilized in this study was derived from diagnostic submissions and hence cannot be considered prevalence data. For each case, there were multiple sources of bias that make standardization and objective interpretation of VDL data very difficult. First, information is limited to the submission sheet, submitted specimens, and tests requested or the VDL diagnostician’s decision on testing. Each case did not test for all possible causes of lameness and the case search criterion focused on arthropathies. Since the completion of this analysis, multiple case reports have highlighted neurological and vesicular viral pathogens as important lameness etiologies, which were beyond the scope of this retrospective study at the time.10-14 Furthermore, the analysis was focused on infectious arthritis, specifically MHS, and the MHS case definition targeted acute cases. This study also did not include sows, boars, gilts, suckling, or nursery pigs; all of which contend with diverse lameness challenges.

Additionally, the retrospective case review process involves subjective steps completed by the veterinarian, laboratory technician, diagnostician, and case reviewer. For example, a diagnostician may interpret histopathologic findings differently depending upon their experience, current or popular health priorities within the industry, areas of expertise, and information provided about the case by the submitting veterinarian.

This retrospective study generated information that can support clinicians when diagnosing lameness in the field and when submitting lameness cases to a VDL. For example, this study quantifies the number of investigations that did not reveal a clear diagnosis (lameness with inconclusive findings) which is important for veterinarians to understand when developing a diagnostic plan for lameness and when communicating that plan to producers. This study also highlights that diverse etiologies contributed to the cause of lameness in the majority of cases. The role of infectious agents, such as MHS, have been heavily emphasized in contributing to lameness, however this retrospective study suggests that for cases submitted to the laboratory, MHS was not found in a majority of cases. In terms of summarizing submission information for lameness cases, this study provides information on diagnostic submission habits that was previously not available. This information can serve as useful talking points when completing lameness submissions with a producer and outlines potential expectations for lameness diagnostic plans.

Implications

- In this study, the four diagnostic categories of lameness with inconclusive findings, MHS, metabolic bone disease, and bacterial infection comprised 77.8% of the cases.

- Examination of the submission sheet and diagnostic results for the MHS cases revealed varied approaches to MHS diagnosis with respect to the amount of information provided to the lab, number of tests requested, and number of specimens submitted for diagnostics.

- This study reinforces the importance of careful clinical examination, proper sampling, and confirming causes with appropriate diagnostic testing for accurate diagnosis of lameness.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the ISU VDL staff, including information technology support for their assistance in creating the case database. Thank you to the Swine Medicine Education Center staff and interns. Thank you to Dr Bailey Arruda and Dr Maria Clavijo for input on search strategy. The National Pork Board, Iowa Pork Producers Association, Swine Medicine Education Center, and PIC provided funding for this project.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Disclaimer

Scientific manuscripts published in the Journal of Swine Health and Production are peer reviewed. However, information on medications, feed, and management techniques may be specific to the research or commercial situation presented in the manuscript. It is the responsibility of the reader to use information responsibly and in accordance with the rules and regulations governing research or the practice of veterinary medicine in their country or region

References

1. Thacker E, Minion FC. Mycoplasmosis. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:804-822.

2. Torrison JL. Optimizing Diagnostic Value and Sample Collection. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:92-101.

3. Hagedorn-Olsen T, Basse A, Jensen TK, Nielsen NC. Gross and histopathological findings in synovial membranes of pigs with experimentally induced Mycoplasma hyosynoviae arthritis. APMIS. 1999;107:201-210.

4. Hagedorn-Olsen T, Nielsen NC, Friis NF, Nielsen J. Progression of Mycoplasma hyosynoviae infection in three pig herds. Development of tonsillar carrier state, arthritis and antibodies in serum and synovial fluid in pigs from birth to slaughter. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 1999;46:555-564.

5. Gomes Neto JC, Gauger PC, Strait EL, Boyes N, Madson DM, Schwartz KJ. Mycoplasma-associated arthritis: Critical points for diagnosis. J Swine Health Prod. 2012;20:82-86.

*6. Schwartz K. Preconference seminar oral presentation: Infectious causes of lameness. Proc AASV. Orlando, Florida. 2015:7-18.

7. Buttenschon J, Svensmark B, Kyrval J. Non-purulent arthritis in Danish slaughter pigs. I. A study of field cases. J Vet Med Series A. 1995;42:633-641.

*8. Nielsen EO. Diagnosis of lameness in slaughter pigs by autopsy and culture from joints. Proc IPVSC. Melbourne, Australia. 2000;95.

9. Torrison JL. Nervous and Locomort Systems. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:319-353.

10. Leme RA, Zotti E, Alcântara BK, Oliveira MV, Freitas LA, Alfieri AF, Alfieri AA. Senecavirus A: An emerging vesicular infection in Brazilian pig herds. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015;62:603-611.

11. Montiel N, Buckley A, Guo B, Kulshreshtha V, VanGeelen A, Hoand H, Rademacher C, Yoon KJ, Lager K. Vesicular disease in 9-week-old pigs experimentally infected with Senecavirus A. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1246-1248.

12. Segalés J, Barcellos D, Alfieri A, Burrough E, Marthaler D. Senecavirus A. Vet Pathol. 2017;54:11-21.

13. Arruda PH, Arruda BL, Schwartz KJ, Vannucci F, Resende T, Rovira A, Sundberg P, Nietfeld J, Hause BM. Detection of a novel sapelovirus in central nervous tissue of pigs with polioencephalomyelitis in the USA. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64:311-315.

14. Arruda BL, Arruda PH, Magstadt DR, Schwartz KJ, Dohlman T, Schleining JA, Patterson AR, Visek CA, Victoria JG. Identification of a divergent lineage porcine pestivirus in nursing piglets with congenital tremors and reproduction of disease following experimental inoculation. PLoS One. 2016;24:11:e0150104. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150104.

* Non-refereed references.