| Original research | Peer reviewed |

Cite as: Costa MO, Ek CE, Patterson MH, et al. Subclinical colitis associated with moderately hemolytic Brachyspira strains. J Swine Health Prod. 2019;27(4):196-209.

Also available as a PDF.

SummaryObjective: Microbiological and virulence characterization of 2 moderately hemolytic Brachyspira strains. Materials and methods: Clinical isolates were obtained from diarrheic (3603-F2) and healthy (G79) pigs. Phenotypic characterization included assessment of hemolytic activity on blood agar and biochemical profiling. Genotyping was performed by sequencing the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase (nox) gene, whole genome sequencing, and comparison to relevant Brachyspira. Pig inoculation included 4 treatment groups in 2 challenge experiments: negative control (sterile broth media; n = 12), positive control (Brachyspira hampsonii genomovar 2 strain 30446; n = 18), and 3603-F2 (n = 12) or G79 (n = 12). Fecal scoring and rectal swabbing for culture were performed daily. Animals were euthanized following onset of mucohemorrhagic diarrhea or between 21 and 28 days post inoculation (dpi). Gross and microscopic pathology were assessed. Terminal colon samples were used to characterize post-infection mucosal ion secretion. Results: Both strains were moderately hemolytic. Whole genome and nox sequencing identified 3603-F2 as Brachyspira murdochii and G79 as a novel strain. Both challenge trials revealed intestinal colonization, but no mucohemorrhagic diarrhea. Sporadic watery diarrhea was induced by 3603-F2 associated with a pattern of microscopic lesions similar to pigs with swine dysentery (positive controls). No diarrhea was observed in G79 inoculated pigs, but microscopic lesions were more severe than in controls. Both strains induced greater colonic anion secretory potential than negative controls 21 dpi. Implications: Allegedly avirulent Brachyspira species most closely related to B murdochii can be associated with subclinical colitis and may be a concern for grow-finish pigs. | ResumenObjetivo: Caracterización microbiológica y virulencia de 2 cepas de Brachyspira moderadamente hemolíticas. Materiales y métodos: Se obtuvieron aislados clínicos de cerdos diarreicos (3603-F2) y sanos (G79). La caracterización fenotípica incluyó la evaluación de la actividad hemolítica en agar sangre y el perfil bioquímico. La genotipificación se realizó mediante la secuenciación del gen nicotinamida adenina dinucleótido oxidasa (nox), la secuenciación del genoma completo y la comparación con Brachyspira relevante. La inoculación de cerdos incluyó 4 grupos de tratamiento en 2 experimentos de desafío: control negativo (medio de caldo estéril; n = 12), control positivo (Brachyspira hampsonii genomavariante 2 cepa 30446; n = 18) y 3603-F2 (n = 12) o G79 (n = 12). La puntuación fecal y el hisopado rectal para el cultivo se realizaron diariamente. Los animales fueron eutanasiados después de la aparición de diarrea mucohemorrágica o entre 21 y 28 días después de la inoculación. Se evaluó la patología macroscópica y microscópica. Se utilizaron muestras de colon terminal para caracterizar la secreción de iones de la mucosa después de la infección. Resultados: Ambas cepas fueron moderadamente hemolíticas. La secuenciación del genoma completo y la secuenciación del nox identificaron la 3603-F2 como Brachyspira murdochii y la G79 como una cepa nueva. Ambos desafíos revelaron la colonización intestinal, pero no diarrea mucohemorrágica. La diarrea acuosa esporádica fue inducida por la 3603-F2 asociada a las lesiones microscópicas similares a los cerdos con disentería porcina (controles positivos). No se observó diarrea en cerdos inoculados con G79, pero las lesiones microscópicas fueron más severas que en el grupo control. Ambas cepas indujeron un mayor potencial secretor de aniones del colon que los controles negativos 21 días después de la inoculación. Implicaciones: La especie supuestamente avirulenta de Brachyspira más estrechamente relacionada con B murdochii puede asociarse con colitis subclínica y puede ser importante en los cerdos de crecimiento y finalización. | ResuméObjectif: Caractérisation microbiologique et de virulence de deux souches de Brachyspira modérément hémolytiques. Matériels et méthodes: Des isolats cliniques furent obtenus de porcs diarrhéiques (3603-F2) et en santé (G79). La caractérisation phénotypique incluait l’évaluation de l’activité hémolytique sur gélose au sang ainsi qu’un profil biochimique. Le génotypage fut effectué par séquençage du gène de la nicotinamide adénine dinucléotide oxydase (nox), le séquençage du génome entier, et par comparaison à des Brachyspira appropriés. L’inoculation de porcs comprenait quatre groupes de traitement dans deux infections expérimentales: témoins négatifs (milieu de culture stérile; n = 12), témoins positifs (Brachyspira hampsonii genomovar 2 souche 30446; n = 18), et 3603-F2 (n = 12) ou G79 (n = 12). Le pointage fécal et un écouvillonnage rectal pour culture ont été effectués quotidiennement. Les animaux furent euthanasiés à la suite du début d’une diarrhée muco-hémorragique ou entre 21 et 28 jours post-inoculation. Les lésions macroscopiques et microscopiques ont été évaluées. Des échantillons de colon terminal furent utilisés afin de caractériser la sécrétion post-infection d’ions provenant de la muqueuse. Résultats: Les deux souches étaient modérément hémolytiques. Le séquençage du génome entier et du gène nox permit d’identifier la souche 3603-F2 comme étant Brachyspira murcochii et G79 comme une nouvelle souche. Les deux infections expérimentales ont permis d’observer de la colonisation intestinale, mais pas de diarrhée muco-hémorragique. Une diarrhée aqueuse sporadique fut induite par la souche 3603-F2 associée avec un patron de lésions microscopiques similaires à celles de porcs avec de la dysenterie (témoins positifs). Aucune diarrhée ne fut observée chez les porcs inoculés avec la souche G79, mais les lésions microscopiques étaient plus sévères que chez les animaux témoins. Les deux souches ont induit un plus grand potentiel sécrétoire d’anions que les témoins négatifs au jour 21 post-inoculation. Implications: Des espèces de Brachyspira supposées avirulentes et apparentées de près à B murdochii peuvent être associées à de la colite subclinique et représentées un souci chez les porcs en période de croissance-finition. |

Keywords: swine, swine dysentery, colitis, subclinical diarrhea, spirochetosis

Search the AASV web site

for pages with similar keywords.

Received: March 8, 2018

Accepted: February 20, 2019

Before current molecular techniques were employed for bacterial characterization, strong β-hemolysis on culture plates was suggested as an indicator of virulence for Brachyspira species.1-3 Further characterization of Brachyspira species using biochemical profiling was also subject to discussion, culminating with the identification of atypical isolates based on molecular methods.4,5 These atypical isolates are often recovered from pigs with diarrhea, including allegedly non-pathogenic species which display weak to strong β-hemolysis activity or strains of pathogenic Brachyspira species that do not induce strong β-hemolysis.6-10 This knowledge gap on Brachyspira virulence determinants led to the characterization of Brachyspira murdochii strains from diarrheic and healthy pigs across the globe.4,6-8

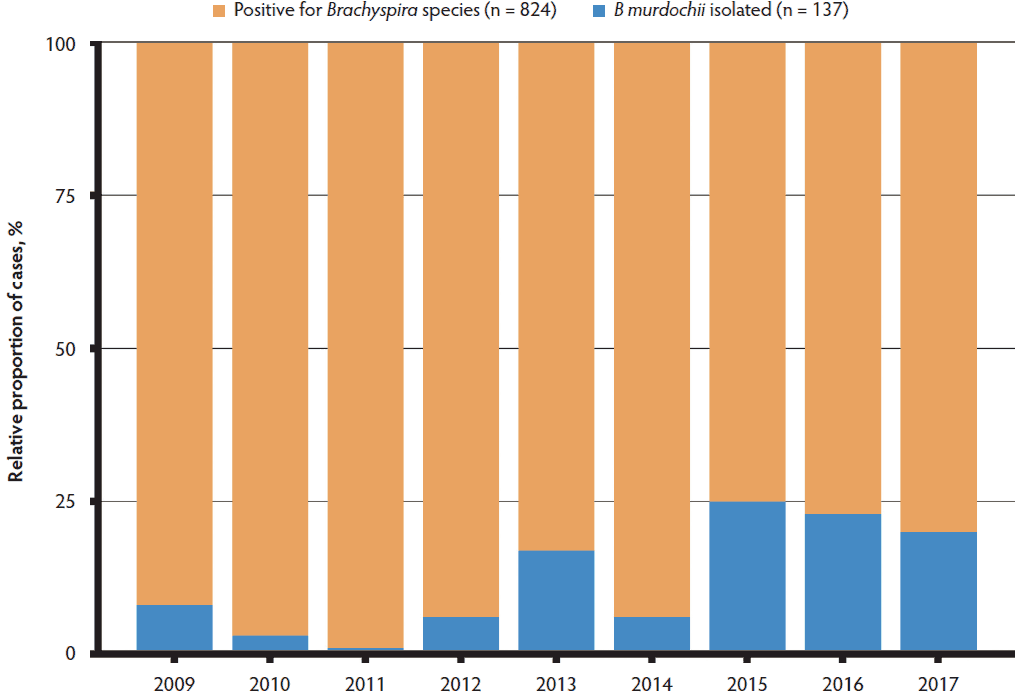

In western Canada, diagnostic surveillance during the past 8 years has revealed an increasing proportion of B murdochii cases associated with clinical diarrhea (Figure 1). A recent investigation led to the identification of two unique Brachyspira isolates: 3603-F2 was recovered from pig feces submitted to the Molecular Microbiology Research Laboratory at the University of Saskatchewan following a diagnostic investigation of watery diarrhea in a grow-finish farm and G79 recovered from a rectal swab of a healthy grower pig in a grow-finish commercial operation with a history of severe Brachyspira hampsonii-associated colitis. Both farms were in central Saskatchewan, Canada6 but had no known epidemiological link. Both Brachyspira strains were initially identified as closely related to B murdochii based on partial sequencing of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase (nox) gene, a commonly utilized gene target for Brachy-spira identification.11 Based on the unusual presentation of the previously mentioned isolates, the objectives of this study were to conduct a detailed phenotypic and genotypic characterization of the isolates and to evaluate their pathogenicity in susceptible pigs using an experimental challenge model. Pathogenicity evaluation included the use of electrophysiology to investigate changes in the colonic function. This is a more objective approach than histopathology, as a measurement of absorptive and secretory capacities are generated.12 Here we hypothesize that these 2 Brachyspira isolates affect colonic secretory and absorptive function, despite minimal observed histological changes.

Figure 1: Relative proportion of cases in western Canada associated with Brachyspira murdochii based on all samples positive for any Brachyspira species in western Canada from January 1, 2009 to September 30, 2017.

Materials and methods

This work was designed and conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council for Animal Care and approved by the University Animal Care Committee at the University of Saskatchewan (Protocol No. 20130034).

Bacterial strains and cultivation

Bacterial isolation and culture were performed as previously described.6 Briefly, fecal samples were plated on selective blood agar (BJ), and incubated anaerobically at 42° C for 96 hours.13 Brachyspira 3603-F2 (hereafter 3603-F2) was isolated from an 11-week-old pig presenting with watery diarrhea (no mucus or blood) at the time of collection. Brachyspira G79 (hereafter G79) was isolated from a rectal swab from a healthy 23-week-old pig.6

Phenotypic characterization of isolates

Isolates were grown in JBS broth (brain heart infusion with 5% [vol/vol] fetal calf serum, 5% [vol/vol] sheep’s blood, and 1% [wt/vol] glucose) for biochemical profiling. An aliquot of 3 mL of 48-hour broth culture from each isolate was pelleted and washed twice with API zym suspension medium before being diluted to an optical density of 5 (MacFarland standard) supplied with the API zym kit (bioMerieux Inc, Durham, North Carolina). Isolates were then tested for enzymatic activity using API zym kit strips as suggested by the manufacturer. A second aliquot from each isolate culture (1 mL) was pelleted, washed twice and re-suspended in 0.85% saline for spot indole and hippurate broth assays, which were performed as previously described.14 Isolate β-hemolysis activity was evaluated while grown on Columbia agar containing 5% sheep blood. Strong hemolysis was characterized by the formation of depigmented translucent areas on agar, whereas weak hemolysis meant pigmented, opaque areas. Hemolysis falling between these extremes (strong, weak) were considered moderate β-hemolysis. Type strains Brachyspira hyodysenteriae ATCC 27164T, B murdochii ATCC 51284T, and Brachyspira pilosicoli ATCC 51139T were included as controls and for further comparisons in all tests.

nox amplification and sequencing

Partial nox sequences were amplified using Brachyspira genus-specific primers as previously described.11 Amplicons were purified using a commercial kit (EZ-10 spin column PCR product purification kit, Bio Basic Canada Inc, Markham, Ontario, Canada) and sequenced using the amplification primers. Raw sequence data was assembled and edited using Pregap4 and Gap4, sequence alignments were performed with CLUSTALw, and phylogenetic trees were calculated in PHYLIP using the F84 distance matrix and neighbor-joining methods.15,16

Whole genome sequencing

For each isolate, genomic DNA was extracted and purified from 3 mL of JBS broth culture using a modified salting out procedure.17 Whole genome sequencing was conducted using a shotgun sequencing approach with established manufacturer’s protocols for the Roche GS Junior instrument (454 Life Sciences, Branford, Connecticut). Pyrosequencing data were processed using the default on-rig procedures from 454/Roche and assembled using gsAssembler (454 Life Sciences, Branford, Connecticut). The 3603-F2 and G79 genome sequence similarity to other known Brachyspira species was calculated using Average Nucleotide Identity (ANIm) by MUMmer within the JSpecies software package.18 Virulence gene sequences were aligned to sequences from reference strains using BLASTn.19

Challenge experiment 1 – strain 3603-F2

Pigs. The methods used herein were modified from Costa et al.20 Healthy, 5-week-old barrow pigs (n = 24) of average body weight compared to their cohorts were purchased from a single porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome negative commercial farm in Saskatchewan, Canada with no clinical history of swine dysentery or previous laboratory diagnosis of Brachyspira. Upon arrival at the isolation facility, pigs were randomly allocated to treatment groups using a random number generator. Animals were acclimated for 7 days prior to inoculation. Rectal swabs and feces collected at -5, -2, and 0 days post inoculation (dpi) were cultured on BJ media as previously described to detect any Brachyspira species infection acquired before inoculation on 0 dpi. Pigs were fed a non-medicated, mash starter diet containing wheat, barley, soybean meal, canola meal, vitamins, and minerals ad libitum for the duration of the trial, with the exception of 12 hour fasting periods prior to each of 3 inoculations. Three treatment groups were used: a negative control (sterile broth, n = 6), a positive control (B hampsonii genomovar 2 strain 30446, n = 6) and the experimental group (3603-F2, n = 12). One 3603-F2 challenged pig was removed from the trial at 10 dpi due to an unrelated injury, and all associated data from this pig was excluded from the analyses. Each treatment group was housed in separate animal biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) rooms in a series of 1.2 × 1.8 m2 pens with solid concrete floors. Positive control and treatment pigs were housed 2 pigs/pen, whereas negative controls were housed 3 pigs/pen. Pens were scraped daily but not washed in order to promote fecal-oral transmission of Brachyspira.

Inoculation. On three consecutive days beginning 0 dpi, pigs were sedated using azaperone (6 mg/kg intramuscular; Stresnil, Elanco, Guelph, Canada) and intragastrically inoculated using an 18 French feeding tube. Feed was removed 12 hours prior to each inoculation and was replaced 2 to 3 hours post inoculation to avoid feed aspiration. Each pig from the positive control group or the experimental group received 10 mL of inoculum JBS broth containing 108 genomic equivalents/mL of their respective Brachyspira strain on each day. The negative control group received sterile JBS broth.

Clinical assessment. Observation of clinical signs was performed twice per day to evaluate responsiveness, skin color, body condition, respiratory effort, and fecal consistency of all pigs. Feces were scored from 0 to 4 based on physical appearance and consistency: 0 = normal, formed; 1 = soft, wet cement consistency; 2 = runny or watery diarrhea; 3 = mucoid diarrhea; 4 = bloody diarrhea (with or without mucus). Because clinical observers (n = 3) were not blinded to treatment group, they rotated daily among rooms to minimize observer bias as much as possible. Observers were trained through several previous Brachyspira inoculation trials using the same scoring system. Beginning 5 dpi, fecal samples were collected daily using rectal swabs for culture followed by species identification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Pathology. Pigs were humanely euthanized by cranial captive bolt and exsanguination within 48 hours of displaying mucohemorrhagic diarrhea (fecal score 4) or between 21 and 28 dpi if no diarrhea was observed. Necropsy examination focused on the gastrointestinal tract. Cecum and spiral colon were linearized and longitudinally opened, and the colon was divided into thirds (proximal, apex, and distal). Gross lesion severity was scored based on the presence of characteristic lesions of swine dysentery including hyperemia, congestion, edema, necrosis, fibrin, and mucus by a single pathologist blinded to treatment group. Colonic tissue from the apex spiral colon was collected for Brachy-spira culture, PCR, and sequencing. Colon samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 to 48 hours prior to processing for paraffin embedding. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) and Warthin-Faulkner (WF) staining was conducted on 4 μm sections of embedded tissue. Microscopic lesions in the spiral colon and cecum were scored based on the severity of the inflammation and necrosis: 0 = no lesions; 1 = minimal to mild necrosis of superficial enterocytes with minimal inflammatory infiltrates; 2 = moderate necrosis and attenuation of enterocytes with mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrates; 3 = severe necrosis (erosion or ulceration present) with moderate inflammatory infiltrates predominantly consisting of neutrophils. The presence of Brachyspira-like organisms was scored from 0 to 3 in WF stained sections: 0 = no spirochetes observed; 0.5 = a single gland contained a few spirochetes; 1 = small numbers of spirochetes in multiple glands; 2 = many spirochetes within several glands; 3 = many spirochetes forming thick mats in numerous glands. After scoring each section, an overall pathology impression score was assigned to each sample. Samples of colon for detection of Salmonella on brilliant green agar following enrichment in selenite broth and ileum for detection of Lawsonia intracellularis by PCR21 were submitted from each animal to Prairie Diagnostic Services Inc for differential diagnostics.

Brachyspira culture of feces. Rectal swabs were plated on BJ and incubated anaerobically using a commercial gas pack (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) at 42° C for 96 hours. Zones of β-hemolysis were semi-quantified after 48 and 96 hours by the number of streaks observed (1+ to 4+) as well as the strength of hemolysis (strong, moderate, or weak). The absence of hemolysis was recorded as culture negative. After 96 hours of incubation, all the plates which were positive for hemolysis were tested through nox sequencing to confirm the species of Brachyspira detected. For analytical purposes, a pig was considered colonized if Brachyspira was isolated from rectal swabs between 5 and 21 dpi.

Challenge experiment 2 – strain G79

Methods for this experiment were predominantly the same as challenge experiment 1, with main differences related to the number and assignment of pigs across the treatment groups. The animals used were from the same source as challenge experiment 1. However, upon arrival to the BSL-2 facility, pigs were blocked by weight and then assigned to different treatment groups. This experiment had 3 treatment groups: negative control (sterile broth, n = 6), positive control (B hampsonii genomovar 2 strain 30446, n = 12) and the experimental group (G79, n = 12). In addition, the clinical observers were blinded to identity of the G79 and positive control groups. Daily fecal samples were collected from 5 to 21 dpi with euthanasia occurring within 48 hours of pigs displaying mucohemorrhagic diarrhea or between 21 and 26 dpi if no mucohemorrhagic diarrhea was observed. All other procedures were performed as described for challenge experiment 1.

Colonic mucosa ion secretory capacity

Positive control pigs from both trials were excluded from the analyses because they were euthanized when they presented with mucohemorrhagic diarrhea (at peak clinical signs). By contrast, pigs in the negative control, 3603-F2 and G79 groups were euthanized at the end of the experiments (after 21 dpi) because they did not develop mucohemorrhagic diarrhea. Therefore, electrogenic secretory analyses included the 3603-F2 inoculated pigs (n = 12), negative controls for 3603-F2 (n = 6), G79-inoculated pigs (n = 12), and negative controls for G79 (n = 6). Briefly, segments of spiral colon (apex region, midpoint between the cecocolic junction and the transversal colon) were harvested immediately after euthanasia. Segments were washed with Krebs buffer (pH 7.4, containing 113 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.6 mM Na2HPO4, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4•H2O, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.1 mM MgCl2•6H2O, 2.2 mM CaCl2•2H2O, and 10 mM glucose) chilled to 4° C. Samples were immediately transported to the lab in Krebs buffer gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 where the serosa (visceral peritoneum) and longitudinal and circular muscle layers of the colonic wall were removed. Pieces of stripped mucosa (2-12 tissue replicates of each segment per pig) were then placed on 1 cm2 Ussing chamber inserts and placed into the Ussing chamber (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, California). Each reservoir was independently gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. A heated circulating water bath maintained the bathing buffer in the Ussing chamber constantly at 37° C. Transepithelial potential differences were short-circuited to 0 mV with a voltage clamp using Ag-AgCl electrodes and 3 M KCl agar bridges (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, California) on apical and basolateral sides.

Samples were allowed to equilibrate for 20 minutes before the addition of any drugs. A 1mV pulse every 30 seconds was used to determine the resistance and tissue viability from the resulting current. Changes in short-circuit current (Isc) were measured following tissue exposure to different drugs. After a steady state was reached, 10 µM of the adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (I6504; Sigma Aldrich) was added to both the apical and basolateral sides of the chamber to increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and stimulate cAMP activated channels, such as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR). After a steady state was reached, 0.1 mM of carbachol (C4382; Sigma Aldrich) was added to both the apical and basolateral sides of the chamber. This cholinergic agonist increases intracellular Ca2+ activating calcium dependent ion transport channels. After a steady state was reached, 10 µM of forskolin (F6886; Sigma Aldrich) and 1 mM of 1 M 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; I5879; Sigma Aldrich) were added to the apical and basolateral sides of the Ussing chamber causing a massive irreversible and sustained elevation in cAMP to fully induce cAMP-activated secretion. Finally, after a steady state was reached, 0.1 mM bumentanide (B3023; Sigma Aldrich) was added to the basolateral side of the Ussing chamber to inhibit the basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl- co-transporter 1 (NKCC1).

Statistical analysis

Except for the third cluster analyses, the statistical analysis was performed independently for each animal experiment using Prism 7.0c (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California) and Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Potential group differences in the frequency of dichotomized clinical, microbiological and pathological outcome measures (diarrhea, colonized, terminal culture results) were assessed using a Fisher’s exact test. Potential differences in continuous and ordinal outcome measures (days to first fecal culture positive, % fecal samples culture positive) between the Brachyspira inoculated groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate.

A multivariate approach was used to assess potential group differences in histological lesion severity and mucosal secretory capacity. This enabled multiple histological or physiological outcome measures to be compared among the group simultaneously. Three cluster analyses (Ward’s linkage; Euclidean dissimilarity measure) were performed. Histological lesion severity (scaled-ranks of colonic and cecal necrosis and inflammation, WF staining scores) was analyzed separately for each challenge experiment as previously described.22 A third cluster analysis was used to assess potential differences in colonic mucosa ion secretory capacity in the spiral colon using electrical Isc generated in Ussing chambers. For this, negative control, 3603-F2, and G79 pigs were included and the Isc results of multiple tissue replicates were averaged into a composite score for each pig. Data from both challenge experiments were analyzed together to increase the delineating power of the cluster analysis.

For all cluster analyses, the appropriate number of clusters was determined using the post-hoc Duda-Hart Je(2)/Je(1) and Calinski stopping rules. Kruskal-Wallis and post hoc Dunn tests with Sidak multiple comparison adjustments were used to assess how the clusters differed in terms of the underlying histological or ion secretory capacity variables. For all analyses, P < .05 was considered statistically significant a priori.

Results

Microbiological characterization

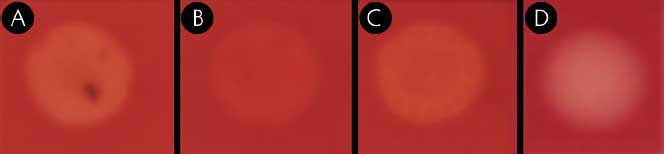

Phenotypic characterization. A summary of the phenotypic characterization results is found in Table 1. β-Hemolytic activity for 3603-F2 and G79 was moderate in both cases, whereas the B murdochii type strain displayed only weak β-hemolysis on blood agar plates (Figure 2). Both test strains and the B murdochii type strain were positive for β-glucosidase activity. The only strain which was positive for the indole spot test and α-glucosidase activity was B hyodysenteriae.

Table 1: Phenotypic profiles of strains 3603-F2 and G79 and other Brachyspira species type strains.

| Isolate | β-hemolysis | Indole | Hippurate | α-Galactosidase activity | α-Glucosidase activity | β-Glucosidase activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B murdochii* | Weak | - | - | - | - | + |

| B hyodysenteriae* | Strong | + | - | - | + | + |

| B pilosicoli* | Weak | - | + | +† | - | - |

| 3603-F2 | Moderate | - | - | - | - | + |

| G79 | Moderate | - | - | - | - | + |

* type strain.

† weak positive.

Figure 2: Degree of hemolysis on selective blood agar plates induced by A) strain G79, moderate; B) Brachyspira murdochii type strain, weak; C) strain 3603-F2, moderate; and D) Brachyspira hampsonii genomovar II strain 30446, strong.

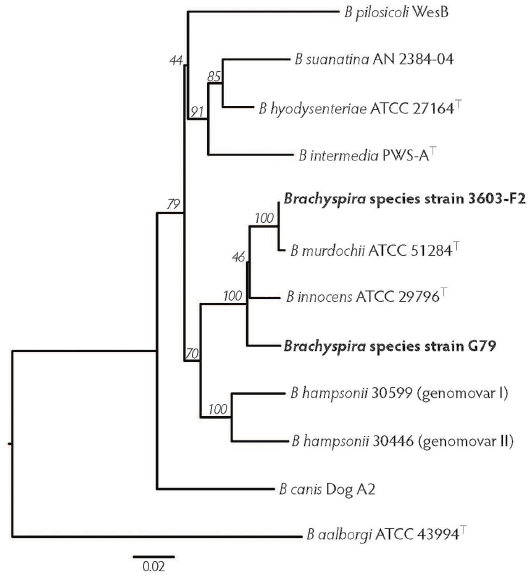

Phylogenetic analysis. Figure 3 is a visual representation of genetic similarities of different Brachyspira species based on the alignment of partial nox gene sequences (801 bp). Strain 3603-F2 clusters with the type strain of B murdochii, as expected since their partial nox sequences were 99% identical to each other. Strain G79 is separated from both Brachyspira innocens and B murdochii with good bootstrap support, as their nox sequence was 97% and 96% similar, respectively. Neither G79 nor 3603-F2 strains clustered near the pathogenic B hyodysenteriae, B hampsonii, or B pilosicoli.

Figure 3: Phylogenetic tree displaying the relatedness of moderately hemolytic Brachyspira isolates 3603-F2 and G79 to the Brachyspira species type strains. This tree is based on an 801 bp alignment of partial nox gene sequences. Bootstrap values are indicated on branches.

Whole genome sequencing. Shotgun sequencing resulted in 154,057 high quality reads (average read length of 478 bp) with 28.04% G/C content for strain 3603-F2, and 182,906 high-quality reads (average read length of 404 bp) with 28.23% G/C content for strain G79. Assembled and annotated genome sequences have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Genbank database with accession numbers JQIU00000000 (G79) and JJMJ00000000 (3603-F2). Table 2 shows the ANIm of strains 3603-F2, G79 in comparison to the complete genome sequences of B hyodysenteriae WA1 (GenBank accession NC_012225), B pilosicoli 95/1000 (NC_014330), Brachyspira intermedia PWS/A (NC_017243), B hampsonii genomovar II (strain 30446, ALNZ00000000), B hampsonii genomovar I (strain 30599, GCA_000334935), Brachyspira suanatina AN4859/03 (GCA_001049755), and B murdochii DSM 12563 (synonym of ATCC 51284T, NC_014150). Whole genome sequences ANIm values of < 95% correspond to different bacterial species as defined by DNA-DNA hybridization.18 The ANIm values ranged from 85.89% to 98.25% between all species. Strain 3603-F2 was found to be 98.25% identical to the B murdochii type strain. Strain G79 was < 95% similar to any Brachyspira species included in the analysis. Its closest relatives were B innocens (93.4%) and B murdochii (93.2%).

Table 2: Whole genome sequence ANIm results based on MUMmer*

| B innocens | B intermedia | B pilosicoli | Strain G79 | Strain 3603-F2 | B hyodysenteriae | B hampsonii 30599 | B hampsonii 30446 | B murdochii | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B suanatina | 86.09 | 93.28 | 86.32 | 86.01 | 86.09 | 92.74 | 89.31 | 88.81 | 86.02 |

| B murdochii | 93.43 | 86.06 | 85.56 | 93.2 | 98.43 | 86.01 | 88.04 | 87.62 | |

| B hampsonii 30446 | 87.65 | 89.01 | 85.6 | 87.63 | 87.67 | 88.78 | 93.63 | ||

| B hampsonii 30599 | 87.86 | 89.44 | 85.62 | 87.89 | 87.88 | 89.27 | |||

| B hyodysenteriae | 86.06 | 91.94 | 86.37 | 86.13 | 86.04 | ||||

| Strain 3603-F2 | 93.51 | 86.33 | 85.5 | 93.03 | |||||

| Strain G79 | 93.42 | 86.05 | 85.68 | ||||||

| B pilosicoli | 85.68 | 86.63 | |||||||

| B intermedia | 86.45 |

* ANI values > 95% have been demonstrated to correspond to different bacterial species as defined by DNA-DNA hybridization. The highest scores for each experimental strain are underlined.

ANIm = average nucleotide identity.

To identify putative hemolysin genes in the genome of strains 3603-F2 and G79, gene sequences of tlyA, tlyB, tlyC, and hlyA from B hyodysenteriae WA1 (NC_012225), a pathogenic strain, were used as a reference in comparison to the studied strains. Predicted open reading frames with significant similarity to all 4 putative hemolysin genes were identified in the genomes of 3603-F2 and G79: tlyA (83% nucleotide identity to both strains), tlyB (87% identity to strain 3603-F2 and 85% to strain G79), tlyC (86% identity to strain 3603-F2 and 84% to strain G79), and hlyA (95% identity to strain 3603-F2 and 86% to strain G79). In parallel, B murdochii (NC_014150) tlyA, tlyB, tlyC, and hlyA sequence similarities to the same B hyodysenteriae were 83%, 88%, 84%, and 95%, respectively. When investigating the G79 and 3603-F2 hemolysin genes’ homology to the non-pathogenic B innocens ATCC 29796 (GCA_000384655), the only gene present in the B innocens genome was tlyA, which had an 85% nucleotide identity to G79 and 84% to 3603-F2.

Strain virulence evaluation

Challenge experiment 1 – strain 3603-F2. A summary of clinical and microbiological findings from this trial are presented in Table 3. Median fecal scores were significantly greater in the 3603-F2 group compared to negative control but none of the pigs in either group developed mucohemorrhagic diarrhea during the study period. However, 5 of 11 (45%) of the 3603-F2-inoculated animals had scattered episodes of watery diarrhea that ceased within 12 hours, while 10 of 11 (91%) of the 3603-F2 pigs were colonized with β-hemolytic spirochetes subsequently identified as strain 3603-F2 by partial nox sequencing. Brachyspira characterized by moderate β -hemolysis was cultured from the colonic mucosa collected at termination from all except one pig (pig 53) from the 3603-F2 group. Interestingly, one pig (pig 61) was culture positive with 2+ β-hemolysis on 6 dpi and developed watery diarrhea on 7 dpi despite having no β-hemolysis observed on blood agar plates from samples collected on that same day. The majority of the positive control B hampsonii inoculated animals (4 of 6, 67%) developed mucohemorrhagic diarrhea as expected, and 5 of 6 pigs in this group became colonized. Partial nox gene sequencing confirmed B hampsonii strain 30446 in terminal colon samples from 4 of 6 (67%) pigs. All samples tested negative for L intracellularis by PCR and Salmonella by isolation.

Table 3: Clinical results from Brachyspira inoculation experiments.

| Challenge experiment 1 | Negative control | Strain 3603-F2 | Positive control (B hampsonii) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. pigs inoculated | 6 | 11‡ | 6 |

| Median fecal score (IQR) | 0.04 (0.13)a | 0.17 (0.07)b | 1.05 (0.81)c |

| Frequency of watery diarrhea | 0/6 | 5/11 (45%) | 0/6 |

| Frequency of mucoid or bloody diarrhea (%) | 0 (0)a | 0 (0)a | 4 (67)b |

| Frequency of colonization/Brachyspira shedding (%)* | NA | 10 (91) | 5 (83) |

| Median days to 1st positive fecal culture (IQR) | NA | 5 (5) | 5 (5) |

| Median % daily fecal samples culture positive (IQR)* | NA | 35.3 (41) | 56.3 (55) |

| Frequency of positive Brachyspira culture at termination (%)‡ | NA | 10 (91) | 4 (67) |

| Challenge experiment 2 | Negative control | Strain G79 | Positive control (B hampsonii) |

| No. pigs inoculated | 6 | 12 | 12 |

| Median fecal score (IQR) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.69) |

| Frequency of watery diarrhea (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) |

| Frequency of mucoid or bloody diarrhea (%) | 0 (0)a | 0 (0)a | 5 (42)b |

| Frequency of colonization/Brachyspira shedding (%)* | NA | 10 (83) | 7 (58) |

| Median days to 1st positive fecal culture (IQR) | NA | 6 (3) | 9 (5) |

| Median % daily fecal samples culture positive (IQR)* | NA | 50 (37) | 11.7 (42) |

| Frequency of positive Brachyspira culture at termination (%)‡ | NA | 6 (50) | 6 (50) |

* Colonization is defined as positive fecal culture between 5 and 21 dpi.

† One pig in 3603-F2 group was removed from the experiment at 10 dpi due to an unrelated injury.

‡ Positive Brachyspira culture on selective media from swab of colonic contents.

a,b,c Superscripts within row differ statistically (P < .05). Exact test was used for frequency variables. Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Mann-Whitney was used for continuous variables.

IQR = interquartile range; NA = not applicable; dpi = days post inoculation.

Necropsy examinations revealed mildly inflamed and hyperemic cecal mucosa in 3 of 11 (27%) 3603-F2-inoculated pigs, but the entire length of the spiral colon had no visible lesions. No other gross lesions were observed in the remaining 3603-F2 inoculated pigs or in the controls. The 2 B hampsonii inoculated pigs that remained healthy also had no gross lesions, but the other 4 pigs presented with mild to severe typhylocolitis with mucohemorrhagic and necrotic exudate.

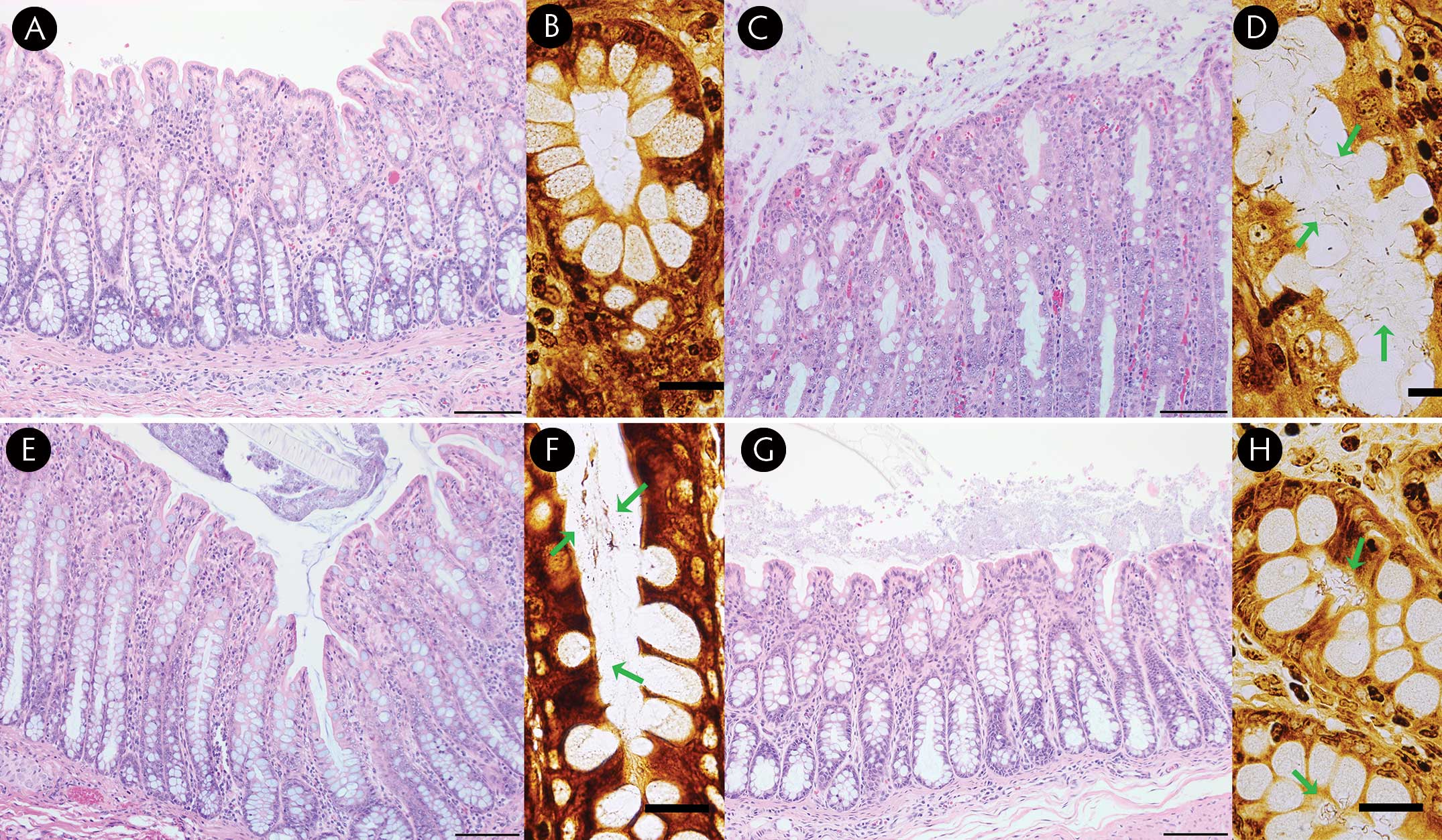

The 3603-F2-inoculated pigs had histologic evidence of mild to moderate inflammation, luminal mucous accumulation, and limited epithelial necrosis throughout the colon and cecum (all scores ≤ 2; Figure 4). Sections from the large intestine of the B hampsonii pigs typically had more severe lesions featuring large mats of mucous and bacteria associated with focal epithelial necrosis. The negative control group had no or mild lesion scores (all ≤ 1). Spirochetes were observed in 11 of 12 colonic sections from 3603-F2-inoculated pigs, whereas the clinically affected B hampsonii-inoculated group had both moderate and large numbers of spirochetes visible. No spirochetes were observed in colonic sections of all negative control pigs, except one with very low numbers.

Figure 4: Hematoxylin and eosin (HE; bar = 200 µm) and Warthin-Faulkner (WF; bar = 20 µm) stained porcine colon from the challenge experiments. A) Negative control pig with normal colon, HE stain. B) Negative control pig with no spirochetes, WF stain. C) Positive control (30446) pig with moderate to severe muconecrotic colitis, HE stain. D) Positive control (30446) pig with many spirochetes in glands (arrows), WF stain. E) Strain 3046-F2 inoculated pig with moderately increased mucus, minimal necrosis and mild colitis, HE stain. F) Strain 3046-F2 inoculated pig with small numbers of spirochetes in glands (arrows), WF stain. G) Strain G79 inoculated pig with a mild mucus increase and minimal colitis, HE stain. H) Strain G79 inoculated pig with occasional glands containing many spirochetes (arrows), WF stain.

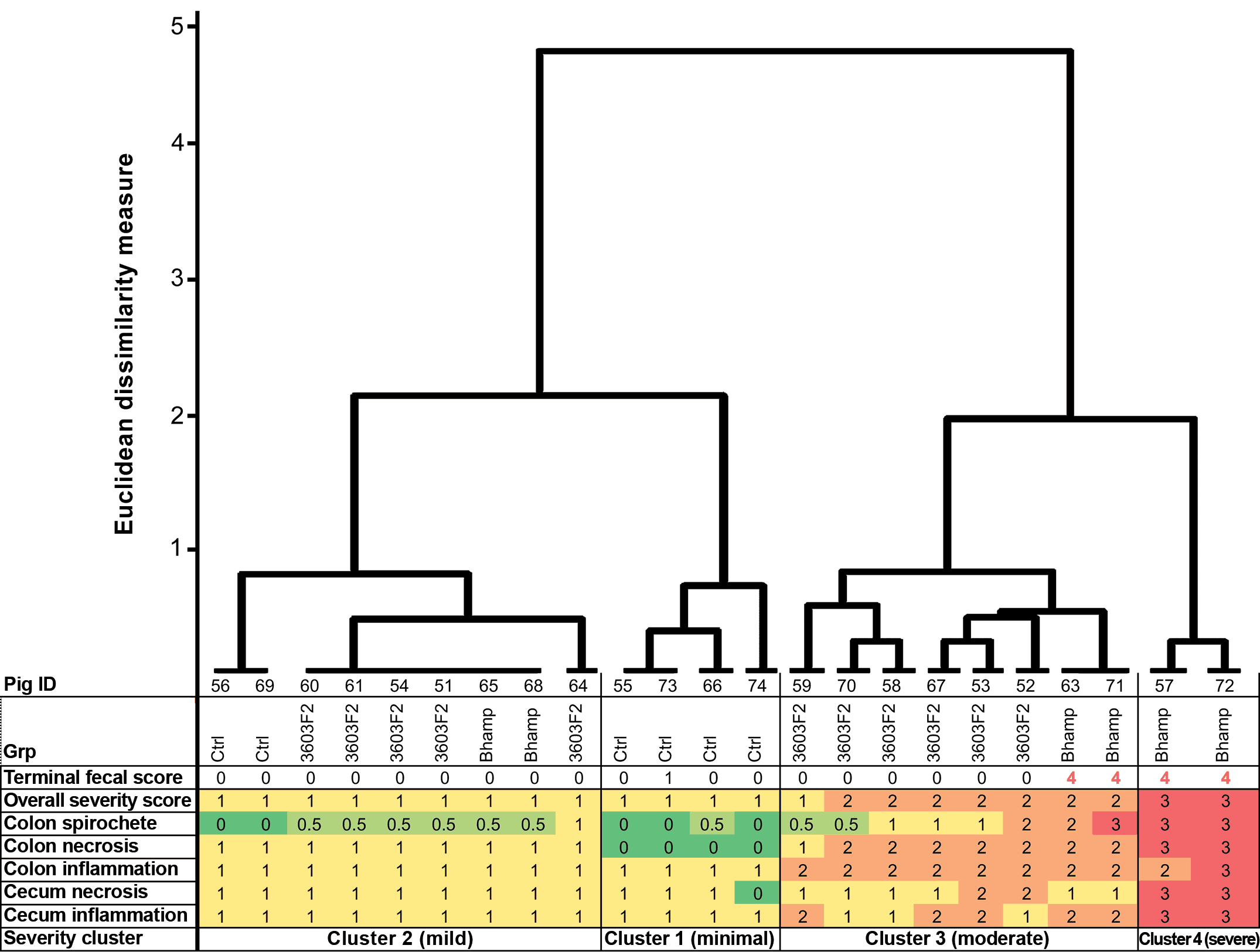

Using cluster analysis, pigs were assigned to 1 of 4 ‘severity clusters’ based on the severity of histological lesions in the colon and cecum and their colonic spirochete score (Figure 5). Two of the 4 B hampsonii inoculated pigs with mucohemorrhagic diarrhea at termination comprised the highest severity cluster (cluster 4). Six 3603-F2 inoculated pigs were grouped in cluster 3 (moderate severity) along with the other 2 B hampsonii pigs that had mucohemorrhagic diarrhea at termination. Cluster 3 mainly featured pigs with moderate colonic inflammation and necrosis. The remaining five 3603-F2 inoculated pigs were grouped within cluster 2 (mild severity) along with 2 negative-control and 2 non-diarrheic B hampsonii pigs. Severity cluster, however, was not associated with fecal shedding.

Figure 5: Dendrogram displaying 3603-F2 challenge trial cluster analysis of the severity of histological lesions in large intestine of inoculated pigs. Twenty-four pigs from 3 inoculation groups (negative control [Ctrl], positive control B hampsonii genomovar II strain 30446 [Bhamp], Brachyspira strain 3603-F2 [3603-F2]) are arranged into 4 lesion severity clusters based on the severity of colonic and cecal inflammation and necrosis (scored 0-3 for each pig) and a semi-quantitative assessment of spirochetes in proximity of colonic epithelium based on examination of Warthin-Faulkner stained slides (scored 0-3). The cluster analysis uses Ward’s linkage and Euclidean dissimilarity measure and was performed on scaled-ranks of severity scores as described by Kaufman and Rousseeuw.22 Terminal fecal scores (0 = formed to 4 = mucohemorrhagic diarrhea) are included to show consistency of feces on the morning before necropsy.

Challenge experiment 2 – strain G79. A summary of clinical and microbiological findings for this trial is presented in Table 3. Positive control (B hampsonii strain 30446) pigs developed mucohemorrhagic diarrhea (5 of 12, 42%). None of the negative control animals developed any clinical diarrhea (mucohemorrhagic or otherwise) during the experimental period. Five of 12 G79 inoculated pigs, and 2 of 4 control pigs developed one or more days of intermittent mild diarrhea of wet cement consistency. Despite observing mucohemorrhagic diarrhea in B hampsonii-inoculated pigs, median fecal scores did not differ across group (P = .08), largely because the pigs developing mucohemorrhagic diarrhea did so very acutely then were terminated. Ten of 12 (83%) G79-inoculated pigs, and 7 of 12 (58%) B hampsonii strain 30446 pigs became colonized by their respective inocula strain. At termination, colonic contents from 6 of 12 (50%) G79 and 6 of 12 (50%) B hampsonii group animals were culture-positive for their respective inoculum species, confirmed by partial nox gene sequencing. None of the negative control animals shed β-hemolytic bacteria at any point during this study. All samples were negative for L intracellularis by PCR.

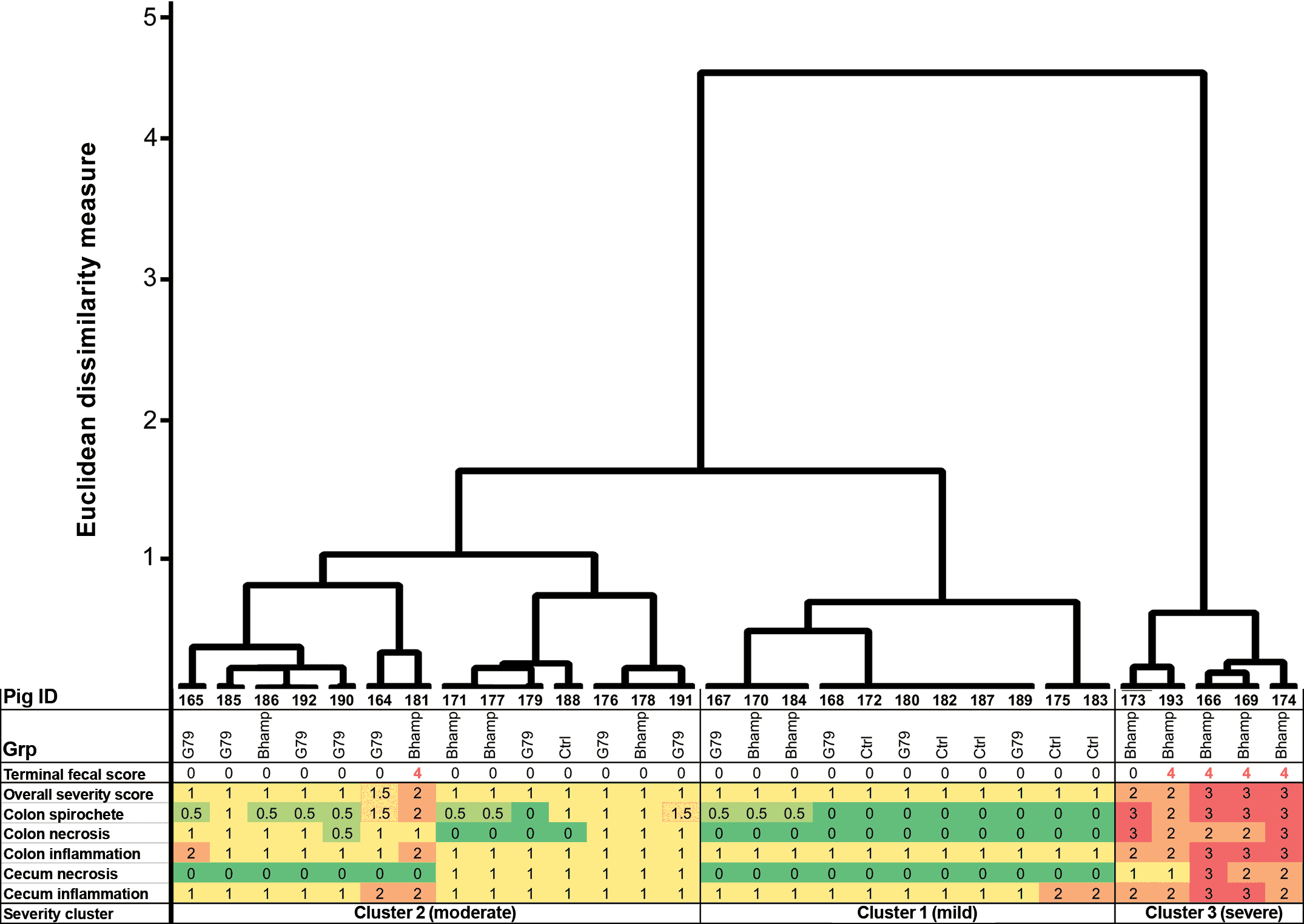

Necropsy examination of G79-inoculated and negative control pigs revealed no visible gross abnormalities in ceca and large intestines, whereas 6 of 12 (50%) B hampsonii pigs had moderate to severe, multifocal to diffuse colitis associated with mucohemorrhagic and fibrinonecrotic lesions consistent with swine dysentery. Histological lesions were severe in the B hampsonii-inoculated pigs with 6 of 12 (50%) showing moderate to severe inflammation and necrosis of their colonic and cecal mucosa. By contrast, histopathology was milder in the G79-inoculated and negative control pigs, consistent with the lack of gastrointestinal clinical signs. Animals were grouped into 3 clusters based on their histological lesion severity and spirochetal scores (Figure 6). Five of 12 B hampsonii inoculated pigs, including 4 with mucohemorrhagic diarrhea at termination and 1 non-diarrheic B hampsonii pig (pig 173) grouped in the highest severity cluster (Cluster 3). The moderate severity cluster (Cluster 2) comprised the remaining B hampsonii pigs, the majority (8 of 12) of G79 pigs, and 1 negative control animal. The low severity cluster (Cluster 1) comprised the majority (5 of 6) of control pigs, as well as 4 of 12 G79 and 2 of 12 B hampsonii inoculated pigs, all of which were clinically normal at termination except 1 B hampsonii inoculated pig (pig 181) that had mucohemorrhagic diarrhea of 1-day duration at the time of necropsy (an acute case).

Figure 6: Dendrogram displaying G79 cluster analysis of the severity of histologic lesions in large intestine of inoculated pigs. Thirty pigs from 3 inoculation groups (negative control [Ctrl], positive control B hampsonii genomovar II strain 30446 [Bhamp], Brachyspira strain G79 [G79]) are arranged into 3 lesion severity clusters based on the severity of colonic and cecal inflammation and necrosis (scored 0-3 for each pig) and a semi-quantitative assessment of spirochetes in proximity of colonic epithelium of Warthin-Faulkner stained slides (scored 0-3). The cluster analysis uses Ward’s linkage and Euclidean dissimilarity measure and was performed on scaled-ranks of severity scores as described by Kaufman and Rousseeuw.22 Terminal fecal scores (0 = formed to 4 = mucohemorrhagic diarrhea) are included to show consistency of feces on the morning before necropsy.

Colonic mucosa ion secretory capacity

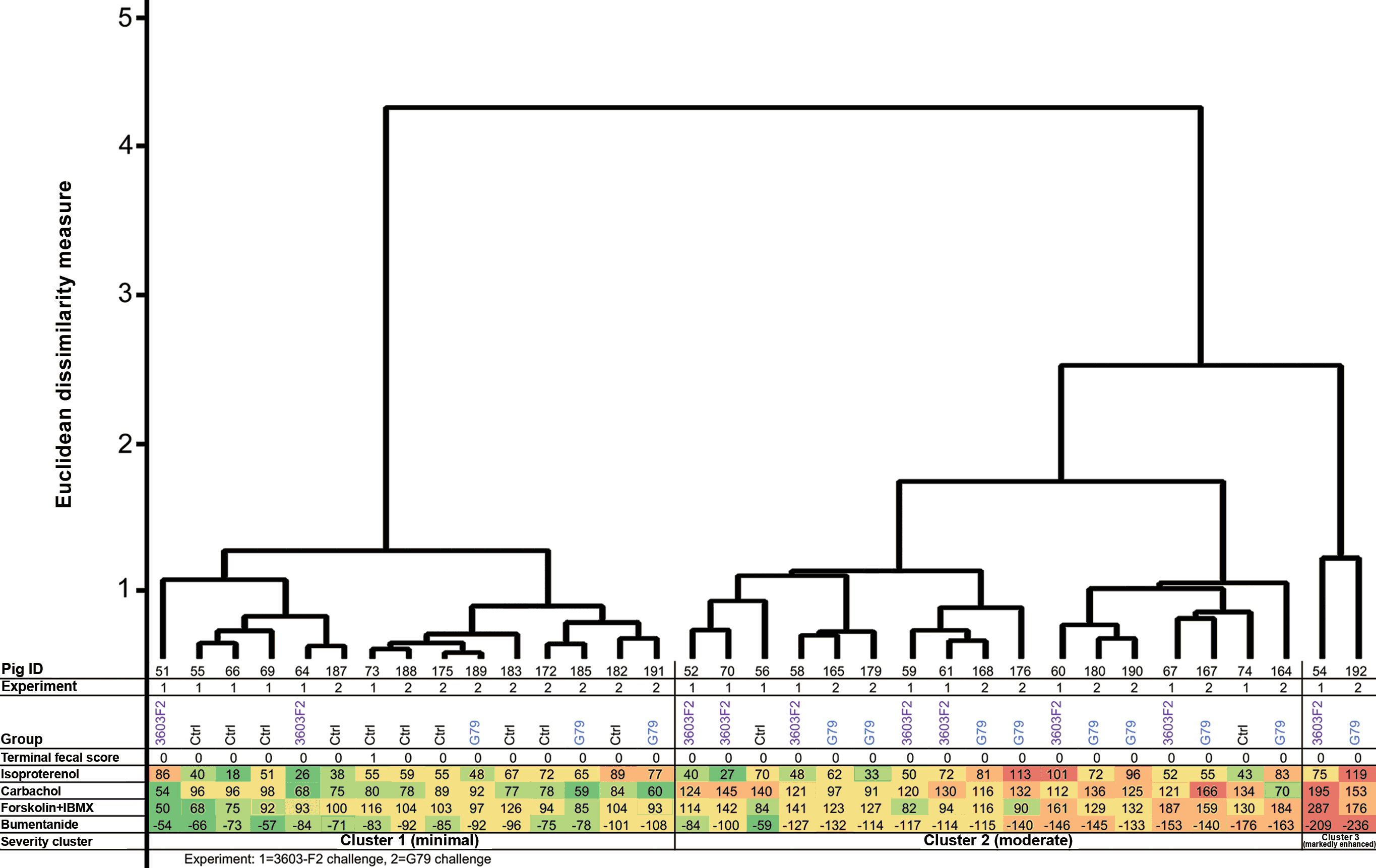

The electrogenic anionic secretory response of spiral colon (apex) mucosa was investigated in pigs inoculated with both tested strains (3603-F2 and G79) and negative controls in Ussing chambers by characterizing changes in Isc following the movement of ions between the apical (luminal) and basolateral (stromal or circulation) aspects of the colonic epithelium. Each of the 4 drugs used stimulated or inhibited a different ion channel pathway, and collective responses were used to assess an increase or decrease in intestinal secretion in ex vivo tissues. Although no pigs had diarrhea when the colonic mucosal tissues were collected for Ussing chamber analyses, their secretory responses grouped into 3 distinct clusters (normal, moderate, and markedly enhanced; Figure 7). There were clear differences between the Brachyspira-inoculated and negative control pigs but the 3603-F2 and G79 inoculated pigs had similar responses. The majority of 3603-F2 (8 of 10) and G79 (9 of 12) inoculated pigs had moderately or markedly enhanced secretory responses (positioned in clusters 2 or 3) compared to the majority of negative control pigs (10 of 12) which grouped into cluster 1, considered normal. Specifically, pigs in clusters 2 and 3 had greater responses to isoproterenol (an adrenergic stimulator of CFTR chloride secretion), carbachol (stimulator of calcium-activated chloride channels), forskolin/IBMX (direct stimulation of CFTR-based chloride secretion), and bumentanide (inhibitor of basolateral to apical chloride movement through Na+-K+-2Cl- co-transporters).

Figure 7: Cluster dendogram displaying analysis of the colonic secretory capacity in Brachyspira inoculated pigs. Thirty-four pigs from 3 inoculation groups (negative control [Ctrl], Brachyspira strain G79 [G79], and Brachyspira strain 3603-F2 [3603-F2]) are arranged into 3 clusters based on their secretory responses. Specifically, the intensity of ion movement through the mucosa for each pig is represented numerically, measured by the change in a short-circuit current (Isc). Experiment 1 reflects challenge trial 1 (strain 3603-F2) and experiment 2 reflects challenge trial 2 (strain G79). The cluster analysis uses Ward’s linkage and Euclidean dissimilarity measure. Terminal fecal scores (0 = formed to 4 = mucohemorrhagic diarrhea) are included to show consistency of feces on the morning before necropsy which was performed 3 to 4 weeks post inoculation.

Discussion

Spirochetes of the Brachyspira genus are of interest to the pork industry due to their ability to cause mucoid or hemorrhagic diarrhea. Three species, B hyodysenteriae, B pilosicoli and B hampsonii, have targeted diagnostic tests available in most diagnostic laboratories due to their clinical and economic significance. Since 2009, western Canada submissions by veterinarians revealed a growing number of samples positive for B murdochii in feces of colonic tissue samples. The characterization of 2 such Brachyspira isolates, which by many would be considered non-pathogenic and non-production limiting, is described here. Both isolates were identified as closely related to B murdochii by sequencing of the nox gene, and speciation by whole genome sequencing revealed similar results. Strain G79 was recovered from a healthy grower pig on a farm with a clinical history of severe mucohemorrhagic diarrhea associated with B hampsonii. Strain 3603-F2 was isolated from a diagnostic sample collected from a pig with diarrhea. In the current study, neither strain caused mucohemorrhagic diarrhea, but they were also not avirulent, which is a relevant finding for the western Canadian swine industry. Strain 3603-F2 induced microscopic lesions similar to, albeit less severe than, B hampsonii along with sporadic episodes of watery diarrhea in roughly half of the inoculated pigs. The G79 strain induced a histopathologic lesion pattern more severe than control pigs, but only sporadic loose stool (consistency of wet cement) in a small number of pigs and overall fecal scores no more severe than controls. While pigs inoculated with either strain had intestinal secretory responses that were greater than controls, it must be emphasized that these responses were measured 3 to 4 weeks after inoculation and may be different if measured during periods of loose or watery feces. However, most of the 3603-F2 or G79 inoculated pigs had secretory responses that differed from negative control pigs. Whether or not these pathological and physiological changes would result in diarrhea in commercial farms is not fully understood, but it is noteworthy that 3603-F2 was originally isolated from a pig with diarrhea submitted to our diagnostic laboratory. Moreover, pigs on many grow-finish farms have been observed with sporadic mild diarrhea or loose feces, but diagnostics including specialized culture for Brachyspira are rarely performed. Therefore, novel Brachyspira strains, such as 3603-F2 and G79, are unlikely to be identified even though they may be associated with subclinical colitis and mild diarrhea.

Brachyspira murdochii has been previously reported to account for 9.4% to 25.3% of all Brachyspira isolated from diagnostic surveillance cases.5,23 In contrast, we have observed an increasing proportion of cases positive for B murdochii in the last 6 years (range, 1.3%-25.1%), in comparison to all submitted samples suspicious of Brachyspira infection. This disparity may be due to different diagnostic approaches used. Commercial diagnostic laboratories offer bacterial species-specific PCRs targeting only the proven pathogenic Brachyspira species, whereas the data shown in Figure 1 are based on an untargeted approach including culture on selective agar followed by PCR and sequencing of the nox gene. This combination of methods is more sensitive than a species-specific PCR-only approach,11,20 and allows for the detection of any Brachyspira species and mixed infections. Other authors have reported a high incidence of B murdochii in pigs with chronic wasting disease, as well as catarrhal colitis associated with extensive epithelial colonization by the spirochetes.24,25 These observations provide evidence for the potential role for B murdochii and other moderately hemolytic Brachyspira species in colitis, poor performance, and unthriftiness in the grow-finish barn.

Culture characteristics are useful to detect the presence of Brachyspira within a sample but are insufficient to speciate isolates as observed by others.14,26 Here we described isolates with β-hemolytic capabilities in between strong and weak, thus classified as moderate (Figure 2). Although not a direct indicator of virulence, this phenotypic characteristic maybe helpful to practitioners exploring alternative causes of mild diarrhea and sub-optimal grow-finish performance. The identity of strain 3603-F2 was confirmed to be B murdochii after whole genome sequencing and partial nox sequence analysis. Pigs inoculated with this strain presented with intermittent episodes of watery diarrhea and microscopic lesions. Interestingly, the pattern of microscopic lesions observed in a portion of 3603-F2-inoculated pigs clustered together with pigs that developed mucohemorrhagic diarrhea following inoculation with B hampsonii (Figure 5). Previous reports of pigs with loose stools and colitis associated with the isolation of B murdochii corroborate the pathogenicity of various B murdochii isolates.24,27 Although a clear difference in severity of disease caused by the two strains was described herein, subclinical intestinal disease and sporadic episodes of diarrhea have been shown to affect gut health and pig performance.28

However, as discussed previously, a high load of non-pathogenic spirochetes may be responsible for cases of mild colitis and diarrhea.24,27,29 It is worth noting that in challenge experiment 2, only 5 of 12 (42%) B hampsonii-inoculated pigs developed mucohemorrhagic diarrhea, and one of these had only mild necrotic lesions in the colon. Fecal shedding (reported as frequency of colonization or Brachyspira shedding from positive fecal sample cultures between 5 and 21 dpi) mostly reflects an isolate’s ability to colonize the colon. The lack of clustering between shedding and lesions reported mainly speaks to the ability of a given isolate to cause histopathologic lesions, which we have demonstrated to be mild. However, secretory capacity was still affected (as shown in Figure 7). Furthermore, it is important to remember that we and others observed < 100% morbidity when performing experimental challenges,20,30,31 so this challenge experiment was less effective than normal, despite being performed under similar experimental conditions and season as challenge experiment 1. Furthermore, even though the pathologist was blinded to pig identity for both trials, the distribution of 3603-F2 and B hampsonii pigs, but not control pigs, across histology clusters (Figure 5) had a distinct pen bias indicating that housing and location factors contributed to lesion severity. Thus, it is always important to exercise caution when extrapolating results of challenge experiments, because if repeated, different results may occur.

Comparison of the whole genome sequence of G79 (approximately 3 million bp) to other recognized Brachyspira species corroborated the phylogenetic analysis based on partial nox gene (801 bp) sequences and indicate its distinction from both B innocens and B murdochii. We also investigated the presence of hemolysin genes (tlyA, tlyB, tlyC, and hlyA) in the genomes of 3603-F2 and G79. Orthologues of these putative virulence genes were identified in the genomes of both strains. It is important to stress that the role of these hemolysins in the pathophysiology of Brachyspira species is still under debate.9,10 At this point, a cautious diagnostic interpretation is warranted in grow-finish diarrhea cases where any weakly or moderately hemolytic Brachyspira is detected since the virulence attributes and pathogenesis of these strains and species are poorly understood. Even with known limitations, the authors strongly believe that animal challenge experiments are the most definitive diagnostic test available but are rarely performed.

In this study, we provided evidence that 2 Brachyspira strains (3603-F2 and G79) induced significant changes in ion transport capacity across the colonic mucosa when compared to negative controls (Figure 7). These changes were characterized by an increased luminal anion secretory potential. Electrolyte secretion by epithelia is coupled with ion, nutrient, and water absorption.32 Augmented luminal anion secretion capacity was identified by stimulation of CFTR (apical anion channel), through indirect (isoproterenol) and direct (forskolin) increased production of cAMP, and inhibition of NKCC1 (basolateral anion channel) by bumentanide. Other pathogens that employ CFTR overstimulation to induce secretory diarrhea include Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli.33,34 Although diarrhea was mild (3603-F2) to non-existent (G79), the change in anion secretory capacity 21 days after infection suggests a persistent, subclinical disease by allegedly non-pathogenic Brachyspira. A previous study reproduced subclinical ileitis under controlled conditions after L intracellularis infection of naïve pigs, resulting in reduced average daily gain (37%-42%) compared to controls.35 This impact in pig performance was estimated to represent a loss of approximately $3.40 per pig in commercial farm settings.36 Together with the histopathology and electrophysiology data presented, it is important to consider that the subclinical colitis caused by Brachyspira has the potential to lead to adverse effects on animal performance (including average daily gain) as seen in subclinical ileitis. The work described here did not aim to investigate the impact of these atypical Brachyspira isolates on weight gain, which would encompass a much different study design (including trials being performed outside a BSL-2 facility, and stocking densities should be similar to those in commercial operations). The authors strongly encourage further investigation on this issue.

For this study, we chose to use a multivariate statistical approach (cluster analyses) rather than more traditional univariate statistical analyses (parametric or non-parametric approaches such as t-tests, ANOVA or Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, etc), due to the small groups sizes and multiple outcomes reflecting overall health of the pigs. Unlike univariate statistical approaches where each outcome is assessed independently, multivariate statistical approaches assess multiple outcome variables simultaneously. For instance, multiple histopathologic scores representing inflammation, infiltration, and necrosis in several intestinal organs were assessed collectively because overall gut health is reflective of the sum of these outcomes. Many multivariate statistical techniques use visualization to assess group differences rather than statistical inference (generation of P values). Univariate and multivariate approaches each have advantages and disadvantages, but both are legitimate if used appropriately. The use of multivariate approaches overcome issues pertaining to multiple comparisons and adjustments (generating P values for numerous outcomes measured on the same pigs and finding some significant by chance), a fundamental problem of applying repeated univariate tests. In multivariate analyses including the cluster analyses used herein, the Euclidean dissimilarity measure is commonly used due to its simplicity. Similar to the standard genomic dendrogram, the Euclidean dissimilarity measure compares the relative length of the vertical lines separating individual animals and clusters, with greater relative length reflecting greater dissimilarity. However, the absolute values of the Euclidean dissimilarity measure (eg, the 0-5 scale along the y-axis of Figure 5) is not directly interpretable in terms of animal physiology or performance. But when combined with a heat map or cluster mat of raw data, the relative distances between animals and clusters allows for meaningful and relevant visual interpretation of the data and potential group differences or trends.

Although not as severe as swine dysentery, the results presented herein provide evidence that Brachyspira strains 3603-F2 and G79 induce microscopic lesions and sporadic clinical disease in susceptible pigs, along with altered mucosal ion transport capacity that may contribute to diarrhea. As the pork industry moves towards reducing the use of antibiotics in production, enteric organisms capable of inducing mild disease will become more relevant. Improved understanding of the production impact and the development of methods to mitigate loses due to subclinical and mild intestinal disease is warranted.

Implications

- Neither B murdochii strain 3603-F2 nor Brachyspira strain G79 caused swine dysentery-like colonic lesions or mucohemorrhagic diarrhea in trial pigs.

- Brachyspira resembling non-pathogenic species induced microscopic lesions in a similar pattern to, but milder than, B hampsonii and B hyodysenteriae

- Changes to the mucosal ion transport capacity following inoculation with allegedly non-pathogenic Brachyspira suggest a subclinical form of colitis.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was generously provided by the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency Ltd (project No. 2013R054R) and the Agriculture Development Fund (project No. 20130138), the University of Saskatchewan Innovation Enterprise, and the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) Research Trust. Summer student stipends were provided by the WCVM Interprovincial Undergraduate Student Research program and an Undergraduate research award by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Conflict of interest

None reported.

Disclaimer

Scientific manuscripts published in the Journal of Swine Health and Production are peer reviewed. However, information on medications, feed, and management techniques may be specific to the research or commercial situation presented in the manuscript. It is the responsibility of the reader to use information responsibly and in accordance with the rules and regulations governing research or the practice of veterinary medicine in their country or region.

References

1. Harris DL, Glock RD, Christensen CR, Kinyon JM. Inoculation of pigs with Treponema hyodysenteriae (new species) and reproduction of the disease. Vet Med Small Anim Clinic. 1972;67:61-64.

2. Kinyon JM, Harris DL, Glock RD. Enteropathogenicity of various isolates of Treponema hyodysenteriae. Infect Immun. 1977;15:638-646.

3. ter Huurne AA, Muir S, van Houten M, van der Zeijst BA, Gaastra W, Kusters JG. Characterization of three putative Serpulina hyodysenteriae hemolysins. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:269-282.

4. Thomson JR, Smith WJ, Murray BP, Murray D, Dick JE, Sumption KJ. Porcine enteric spirochete infections in the UK: surveillance data and preliminary investigation of atypical isolates. Anim Health Res Rev. 2001;2:31-36.

5. Clothier KA, Kinyon JM, Frana TS, Naberhaus N, Bower L, Strait EL, Schwartz K. Species characterization and minimum inhibitory concentration patterns of Brachyspira species isolates from swine with clinical disease. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:1140-1145.

6. Patterson AH, Rubin JE, Fernando C, Costa MO, Harding JC, Hill JE. Fecal shedding of Brachyspira spp. on a farrow-to-finish swine farm with a clinical history of “Brachyspira hampsonii”-associated colitis. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:137. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-9-137

7. Jacobson M, Gerth Löfstedt M, Holmgren N, Lundeheim N, Fellstrom C. The prevalences of Brachyspira spp. and Lawsonia intracellularis in Swedish piglet producing herds and wild boar population. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2005;52:386-391.

8. Osorio J, Carvajal A, Naharro G, Rubio P, La T, Phillips ND, Hampson DJ. Identification of weakly haemolytic Brachyspira isolates recovered from pigs with diarrhoea in Spain and Portugal and comparison with results from other countries. Res Vet Sci. 2013;95:861-869.

9. Mahu M, De Pauw N, Vande Maele L, Verlinden M, Boyen F, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F, Martel A, Pasmans F. Variation in hemolytic activity of Brachyspira hyodysenteriae strains from pigs. Vet Res. 2016;47:66. doi:10.1186/s13567-016-0353-x

10. Mahu M, Boyen F, Canessa S, Zavala Marchan J, Haesebrouck F, Martel A, Pasmans F. An avirulent Brachyspira hyodysenteriae strain elicits intestinal IgA and slows down spread of swine dysentery. Vet Res. 2017;48:59. doi:10.1186/s13567-017-0465-y

11. Rohde J, Rothkamp A, Gerlach GF. Differentiation of porcine Brachyspira species by a novel nox PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2598-2600.

12. Clarke LL. A guide to Ussing chamber studies of mouse intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1151-1166.

13. Jenkinson SR, Wingar CR. Selective medium for the isolation of Treponema hyodysenteriae. Vet Rec. 1981;109:384-385.

14. Fellström C, Gunnarsson A. Phenotypical characterisation of intestinal spirochaetes isolated from pigs. Res Vet Sci. 1995;59:1-4.

15. Staden R, Beal KF, Bonfield JK. The Staden package, 1998. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:115-130.

16. Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-phylogeny inference package (Version 3.2). Cladistics. 1989;5:164-166.

17. Martin-Platero AM, Valdivia E, Maqueda M, Martinez-Bueno M. Fast, convenient, and economical method for isolating genomic DNA from lactic acid bacteria using a modification of the protein “salting-out” procedure. Anal Biochem. 2007;366:102-104.

18. Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19126-19131.

19. Chen Y, Ye W, Zhang Y, Xu Y. High speed BLASTN: an accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7762-7768.

20. Costa MO, Hill JE, Fernando C, Lemieux HD, Detmer SE, Rubin JE, Harding JC. Confirmation that “Brachyspira hampsonii” clade I (Canadian strain 30599) causes mucohemorrhagic diarrhea and colitis in experimentally infected pigs. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:129. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-10-129

21. Jones GF, Ward GE, Murtaugh MP, Lin G, Gebhart CJ. Enhanced detection of intracellular organism of swine proliferative enteritis, ileal symbiont intracellularis, in feces by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2611-2615.

22. Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

23. Verspohl J, Feltrup C, Thiede S, Amtsberg G. Diagnosis of swine dysentery and spirochaetal diarrhea. III. Results of cultural and biochemical differentiation of intestinal Brachyspira species by routine culture from 1997 to 1999. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2001;108:67-69.

24. Komarek V, Maderner A, Spergser J, Weissenböck H. Infections with weakly haemolytic Brachyspira species in pigs with miscellaneous chronic diseases. Vet Microbiol. 2009;134:311-317.

25. Jensen TK, Christensen AS, Boye M. Brachyspira murdochii colitis in pigs. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:334-338.

26. Ohya T, Araki H, Sueyoshi M. Identification of weakly beta-hemolytic porcine spirochetes by biochemical reactions, PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and species-specific PCR. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70:837-840.

27. Weissenböck H, Maderner A, Herzog AM, Lussy H, Nowotny N. Amplification and sequencing of Brachyspira spp. specific portions of nox using paraffin-embedded tissue samples from clinical colitis in Austrian pigs shows frequent solitary presence of Brachyspira murdochii. Vet Microbiol. 2005;111:67-75.

*28. Paradis MA, McKay RI, Wilson JB, Vessie GH, Winkelman NL, Gebhart CJ, Dick CP. Subclinical ileitis produced by sequential dilutions of Lawsonia intracellularis in a mucosal homogenate challenge model. Proc AASV. Toronto, Canada. 2005:189-191.

29. Neef NA, McOrist S, Lysons RJ, Bland AP, Miller BG. Development of large intestinal attaching and effacing lesions in pigs in association with the feeding of a particular diet. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4325-4332.

30. Rubin JE, Costa MO, Hill JE, Kittrell HE, Fernando C, Huang Y, O’Connor B, Harding JC. Reproduction of mucohaemorrhagic diarrhea and colitis indistinguishable from swine dysentery following experimental inoculation with “Brachyspira hampsonii” strain 30446. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57146. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057146

31. Burrough ER, Strait EL, Kinyon JM, Bower LP, Madson DM, Wilberts BL, Schwartz KJ, Frana TS, Songer JG. Comparative virulence of clinical Brachyspira spp. isolates in inoculated pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:1025-1034.

32. Gawenis LR, Hut H, Bot AG, Shull GE, de Jonge HR, Stien X, Miller ML, Clarke LL. Electroneutral sodium absorption and electrogenic anion secretion across murine small intestine are regulated in parallel. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1140-1149.

33. Golin-Bisello F, Bradbury N, Ameen N. STa and cGMP stimulate CFTR translocation to the surface of villus enterocytes in rat jejunum and is regulated by protein kinase G. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C708-716.

34. Kimberg DV, Field M, Johnson J, Henderson A, Gershon E. Stimulation of intestinal mucosal adenyl cyclase by cholera enterotoxin and prostaglandins. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:1218-1230.

35. Paradis M-A, Gebhart CJ, Toole D, Vessie G, Winkelman NL, Bauer SA, Wilson JB, McClure CA. Subclinical ileitis: Diagnostic and performance parameters in a multi-dose mucosal homogenate challenge model. J Swine Health Prod. 2012;20:137-141.

36. Pommier P, Keita A, Pagot E, Duran O, Cloet PR. Comparison of Tylvalosin with Tylosin for the control of subclinical ileitis in swine. Rev Med Vet. 2008;159:579-582.

* Non-refereed reference